Having been born and raised in one of the “white brick” buildings in Chicago’s now-demolished public housing projects in the Cabrini-Green neighborhood, I’d often find myself fantasizing about what scenarios led my family to live in what is now an empty lot in the shadow of a Target building. A large part of that fantasy would revolve around whether I, with hindsight, would make the same choices were I put in their shoes. Serendipitously enough for me, Dot’s Home provides both validation and insight into how housing inequality manifests for people of color in the U.S.

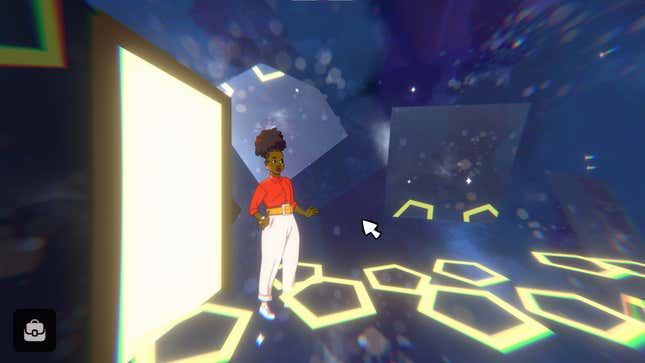

Dot’s Home is a 2D point-and-click narrative game where a 20-year-old named Dorothea “Dot” Hawkins is sent back in time through her family lineage thanks to a mysterious key. To return to the present, Dot must sway her family as they make a multitude of crucial housing decisions in the 50s, 90s, 2010, and in 2021. These branching decisions have major implications for her future housing situation, as well. Along the way, Dot discovers how prevailing systems within housing authorities have plagued not only her family but also many BIPOC that live in the U.S.

Dot’s Home was created by Rise-Home Stories Project, an organization of BIPOC organizers from housing justice advocates, writers, filmmakers, journalists, and game designers. The game explores how BIPOC families end up living where they do today and how much agency they truly had in their journey. Dot’s Home was released on Oct 22, 2021, and is free to play on Steam, Itch.io, Google Play, and the App Store.

I spoke to lead writer and former Kotaku staff writer Evan Narcisse, producer Christina Rosales, and game designer Ryan Huggins about the team’s guiding principles for bringing authenticity into its narrative and what social change they hope to instill in its players.

Dot’s Home serves as one of five media projects from Rise-Home Stories Projects that revolve around families, communities, and how the dominant fixture of the American Dream where you can “pick yourself up by your bootstraps” has been a rigged game for BIPOC families for generations.

Narcisse said one of the reasons exploring the concept of housing inequality worked perfectly for a video game is because games are built systematically by game designers where choices are predetermined for players to navigate, just as housing policies are built for people to traverse.

“When you’re a game designer, you have to think about ‘If I allow the player to do action A, what are consequences B, C, D, E, and F?’ Because of that core design, you can explore systems of power, policy and decision making in a game like this. We’re building a system to talk about a system,” Narcisse told Kotaku.

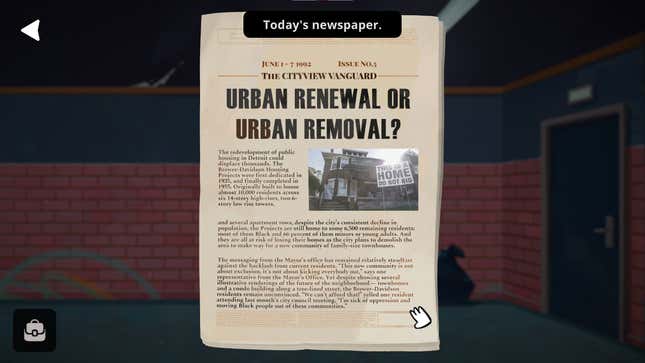

Originally, the game was going to focus on a reality where concepts like redlining never happened and how communities would look as a result of it. The team would later decide to instead have Dot’s Home focus on significant moments in history that affected housing for Black and brown families like the Great Migration, urban renewal, and the foreclosure crisis.

Although red ink isn’t scribbled on a map in the same way as it was in the 30s, Narcisse noted the prevailing attitudes persist today and curtail people’s abilities to buy homes in certain neighborhoods.

“Showing that stuff, moving through a timeline narratively through one family, was how we wanted to explore the idea that some of these things haven’t changed that much,” Narcisse said.

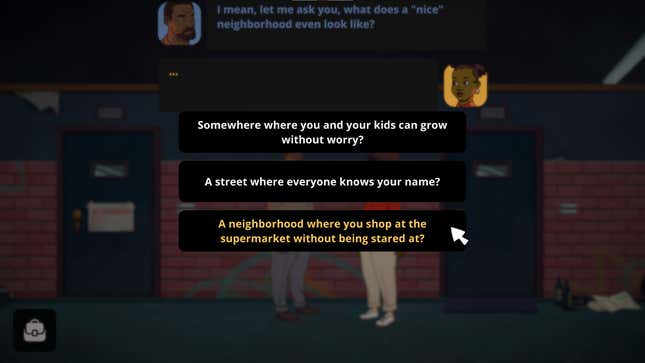

The decision to make Dot’s Home a choice-driven game came about as a method to translate how the illusion of choice in the housing market can feel fixed with restrictive opportunities for autonomy for BIPOC families, like that of a video game developer with players.

“As a player, you might feel like you have the choice to change the course of the future for this family, but ultimately, you don’t. It’s very much a rigged game. You get what you get,” Rosales told Kotaku.

Rosales, who is native Tejana, was told as a child that if she works hard and does all the right things, then she could have a chance at wealth. This idea is something she says many BIPOC know isn’t true. If it were, BIPOC parents would have experienced that wealth generations ago.

Nurturing authenticity that reflected that reality within Dot’s Home stemmed from the elements of the writing team’s family histories, research, and interviews conducted with fair housing historians, law professors, and clients from housing counselors. This effort manifests within the game through its name-dropping of housing terms, including redlining, gentrification repackaged as “urban revitalization,” and deed-in-lieu without talking down to players.

That last term, deed-in-lieu, was a practice that Narcisse was unaware of before working on Dot’s Home. On its surface, deed-in-lieu is like making monthly payments on a home. But if a single payment is missed, the property goes back to the bank.

“It’s a scam, let’s be real. It was run on people of color in cities like Chicago and Detroit during the Great Migration because property owners knew that they were getting a desperate, and maybe sometimes less educated, potential buyer to exploit,” Narcisse told Kotaku.

One theme Dot’s Home introduced has haunted me since I moved back to Chicago: How does one’s individualism run into conflict with collectivism for Black families? Dot quickly transitioned from a character I’d guide as she corrected her timey-wimey debacle, just as I would in a Life Is Strange game, and evolved into a mirror of myself that revealed the harsh truth that many of the decisions I’d made for her family would run in contrast against my family’s reality.

At one of the game’s crossroads, Dot’s father had to decide whether to move his family to the suburbs and leave his best friend Amos behind at their Detroit project building that was set for “urban renewal” or to stick it out and hold the housing authorities to their promise of moving residents back into the community.

Having lived through the same scenario, albeit as a child, I found myself wrestling with what my heart would idealistically desire. I pictured staying in the project building as a sunshine-and-rainbows ending for the family; meanwhile, my reality-worn mind nagged at me with the outcome that befell my family and other residents at Cabrini-Green. Although my mother was lucky in what she dubbed “the lottery” for getting back into the now-gentrified neighborhood, the rest of my family had to relocate to the southside of Chicago or move out of state once the project buildings were demolished, something that felt inevitable for Dot’s family and Amos.

My personal hindsight knew that folding on her family’s dreams of a tight-knit community and rebuilding their home would be easier for them in the long run. Having seen the harrowing signs of inevitable gentrification that my family faced with Cabrini-Green, where the prime real estate proves more advantageous to army recruiters than to Black families, I chose the former for Dot’s family. Dot’s family would move out of the project building and try to make a life in the suburbs without their community.

Rosales said real estate people would tell folks, “You don’t just buy a home; you buy into a community, so be careful with your investment.” But in Dot’s Home, the team wanted to focus on how close-knit communities can become extended families, just like Dot’s father and his friend Amos.

“I’m hungry to think about neighbors that way,” Rosales said. “It’s one of those protective factors that you live close to people and that you kind of know them intimately. That’s valuable. That’s priceless. If we were committed to that ideal, housing would just be more pleasant.”

While planning out Dot’s Home, Rosales played games like Undertale and wanted to emulate how it’s bittersweet ending possibilities could convey how the choices presented to BIPOC families were shadows of the decisions policy-makers constructed for them to choose from.

“Dot says at the end of the game, ‘No matter what we do, we’re always just short of following our dreams.’ And it’s because of all of the cumulative decisions of our past elected leaders, our neighbors, and the people who lived where we are before,” she said.

My choices, which were contradictory to each other depending on the decisions present in each chapter, would ultimately land me with the game’s neutral ending. Out of curiosity, I checked out the “good” and “bad” possibilities that were readily available after finishing the game and was unnerved at the bittersweet nature present across each of them. Rosales said it was easier for the team to come up with the “neutral” and “bad” endings because it is the reality they live in, but constructing a “good” ending felt unnatural to imagine. While a wholly good ending does not exist in Dot’s Home, Rosales more optimistically said it exists in pockets of society, though they are hard to find.

“I wish I lived on a land trust. I wish I lived in a community with others. But it’s not something I can find very easily,” she said. “We’re all pursuing our own opportunities and dreams, so I think we’re all living in this neutral world but the ideal is that we don’t.”

Huggins said a neutral ending might be the most common outcome for players, but it should also teach players to be more daring.

“I think that the nature of getting a neutral ending being kind of like the common route shows us that we need to compromise more. There’s a lot of compromise that goes into everyday living and being able to identify those things,” he said.

Just as no one who played Undertale likely got a good ending on the first try, Huggins said players must actively decide how to make the decisions that might go against their immediate desired outcomes. To get a “good” or “bad” end, he said players might have to go against their own interests.

One piece of media that inspired Huggins in resequencing the game was the 90s educational animated film Our Friend, Martin, where three kids are sent back in time to learn about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. via a string of first-hand meetings. Similar to how the children in the film learn how actions can serve an individual or a community, Huggins said the choice to take actions in Dot’s Home don’t necessarily lead to immediately gratifying results.

“We all make a lot of decisions where we have to think of ourselves as number one, but those always, those tend to come at cost,” Huggins said. “You have to sacrifice to make any decision, and I think it is more poignant with the systemic oppression for people of color because you can’t just go to the person who’s in charge of society and be like, ‘Yo, I don’t like this. Let’s make it better for me specifically.’”

Every time players decide what they think will better the lives of Dot’s family, Huggins said the downwind effects might not be exactly what they expect. Dot ending up in a high-rise apartment in the “bad” ending might enable her to have a modicum of social mobility. But it may not be fulfilling in the same way as if she made riskier decisions for her community that are societally viewed as “worse options.”

Narcisse said he hopes players arrive at the “bad” high-rise ending because it can illustrate how what society deems as individual success can have an adverse effect on one’s well-being if that means they are stripped from their community.

Rise-Home Stories Project cautions players, particularly white folks, to not treat Dot’s Home solely as an exercise in empathy for BIPOC. The goal in making the game was to both validate the realities BIPOC face in the housing market and to have players bear witness to them.

“What we’re asking the player to do is to accompany a family through time, making these decisions and struggling with these decisions and just bearing witness to a family over generations,” she said.

One of the modes of thinking Rosales learned as a social worker that she hopes to instill in Dot’s Home players is the practice of accompaniment. Social workers might not be able to change the system their client is working through and struggling in, but they can accompany them along the way and validate them through a sort of therapeutic alliance.

“My wonky wish for this is that policy makers or the kids of policy makers play this and start to be cynical of why things are the way they are when they don’t have to be,” Rosales said.