As a kid, I used to rush home from school so I could catch the latest episode of the Disney cartoon DuckTales. I loved following Scrooge McDuck and his nephews across the world as they charted a path towards gold and glory, and it was always a blast seeing what new caper they’d stumble into. When I learned a video game adaptation of the series was being developed by Capcom for Nintendo, I couldn’t wait to play it. Released in 1989, the original DuckTales is similar to the Mega Man games, splitting Scrooge’s journey to fill his money bin into five distinct territories he can visit in any order. This takes him from Transylvania to a space station on the moon to the snowy Himalayas. Exploration is a huge part of the gameplay; there’s treasure everywhere and hidden rooms around every corner. Who knew diamonds were a duck’s best friend?

DuckTales is one of those games I still pop in and play. Its sense of adventure, and that of the original cartoon series, inspired me to want to join Disney (which I did in 2014 as my day job, working on some of their animated features). In 2013, a remastered version of DuckTales came out, which is a wonderful homage and expansion of the original game I love. To learn more about the challenges of translating a beloved cartoon into a video game, I spoke with two producers who were in charge of DuckTales on the Disney side of production, David Mullich and Darlene Lacey.

Life Is Like A Hurricane

David Mullich (who I previously interviewed about I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream) joined Disney in 1987 after his own development studio, Electric Transit, closed its doors. He told me via email, “I was pondering what my next move would be when a programmer who used to work for me at another company told me about a job opening at The Walt Disney Company that he thought would be perfect for me. The role was for a ‘Software Development Specialist,’ which sounds like a programming position, but the job description was for what we would now call a Game Producer.”

It was a perfect fit for Mullich, who was a huge Disney fan. “The first film I remember seeing in a movie theater was Mary Poppins, and that film remains a favorite of mine today. I, of course, watched all the Disney animated films as they came to theaters throughout my childhood, and my family made several trips to Disneyland each year. I rode Pirates of the Caribbean not long after it opened, and I was so taken by the attraction that I wanted to be a Disney Imagineer when I grew up. Well, when I went in for my job interview, I had no problem answering one of the questions I was asked: ‘Can you name all seven dwarves?’”

Darlene Lacey’s journey to joining Disney started as a game designer in 1981, when she was 21 and still finishing college. She told me via email, “I worked for AMS (Advanced Microcomputer Systems), which was across the street from the school. We wound up creating Dragon’s Lair there.” Dragon’s Lair is an iconic ‘80s arcade series with incredibly cinematic animation and brutal difficulty. Lacey—who is credited in the game under her maiden name, Waddington—cites the game with launching her career in computer games. She went on to design games for CD-i and LaserDiscs working for Sega of America, before becoming a game producer at Disney in 1989, alongside Sam Palahnuk and Mullich. “Disney Software was Disney’s first serious attempt at entering the computer game market, so it was exciting playing a part in building it from the ground up.”

Mullich was Walt Disney Computer Software’s first staff game producer, which was then a department within Walt Disney Educational Productions. “My first assignment was to head down the street to Walt Disney Studios to enroll in Disney University, a three-day program teaching new employees about Disney history, procedures, and culture. And then, when I graduated it was time to start work, if you can call it work. One day I spent reading a Scrooge McDuck comic book, looking over production stills from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, watching an episode from a new Disney animated television series, and reading a script from a movie Disney wanted to do with Michael J. Fox—all in the name of research. And the next day, my coworkers and I headed over to the studio lot to have our pictures taken with Goofy and Pluto as part of a celebration of a Disney home video movie release. It was quite a magical time.”

Mullich’s main focus was working with Disney’s licensees. The first projects he worked on were with a game company in New York called Hi Tech Expressions, creating the action games Matterhorn Screamer and The Chase on Tom Sawyer’s Island. “These were very simple PC games, that mostly involved me providing them with art reference materials. However, things got more exciting when I moved on to working with NES console game publishers like Capcom, which was developing DuckTales.”

Lacey’s role as a producer meant she was responsible for the oversight of Disney’s own games, as well as titles developed by licensees. “With Disney’s own games, I pitched my own ideas in-house, designed and storyboarded them, then hired a local developer to build them and flesh out the design. I was hands-on with most every part of development except for writing the code itself. I would also typically write copy for the boxes, design the copy protection, weigh in on the box designs, and assist with the development of promotions. I was chiefly responsible for Disney’s value line of software, products that fit on a single 5 ¼’ floppy disk. This included pre-school titles and a series of print kits. I was also working on several large adventure games that never made it, due to Disney Software switching gears later on.”

Lacey also produced the games developed by licensees. “Disney’s policy was for producers to only give these projects a light touch to make sure they stayed on track and were of high enough quality to merit the Disney name. These included the Win, Lose, or Draw games with Hi Tech Expressions, and a series of NES games with Capcom.” Many of the Capcom-develop titles have become Nintendo classics, including Mickey’s Dangerous Chase, Adventures in the Magic Kingdom, Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers, and of course, DuckTales.

Might Solve A Mystery, Or Rewrite History

The DuckTales game came to Disney in the late ‘80s. Disney produced and oversaw the NES game, while Capcom, who had worked with Disney previously on Mickey Mouscapade in 1988, did the actual development. Mullich’s role entailed working with Walt Disney Television Animation to provide Capcom with reference materials from the DuckTales animated show, such as character model sheets, episode scripts, episode screenshots, and music.

“Early in the process, they [Capcom] sent their entire Japanese development team to Burbank to immerse them in Disney culture. During their visit, I took them to Disneyland and gave them a guided tour. Being very proud of my Disney knowledge, I would describe the history of the park and of each ride that we boarded. When the team returned to Japan and began development work, they sent me layouts of each game level, drawn out on paper, for me to approve before actually programming the level. I sent all artwork over to my contact at Disney Character Animation to review. Both myself and another producer at Walt Disney Computer Software, Darlene Lacey, approved it.”

Lacey explained that her role on DuckTales came “at the tail end of development.” She would edit dialog and graphics and do “a lot of game testing. Capcom was overseas, and it wasn’t easy to communicate back then, so I would keep my bug reports and lists of changes as clear and concise as possible and only send them at crucial times, no piecemeal feedback. We would receive e-proms in the mail, test the new versions, write up feedback, and mail back both the e-proms with the list of changes.”

For Lacey, one of the most difficult challenges was “sprucing up the text and dialog to make it fit with the Disney characters, or be grammatically correct while fitting it into the small character limits that we had for displaying the text. It was almost like writing haiku—-how can I express this in the fewest characters possible without awkward line breaks?”

One of the remarkable things about the original DuckTales is how faithful it is to the original TV show. A lot of familiar faces pop up, from Gizmo Duck blasting open a passage on the moon, to Launchpad giving Scrooge a lift over a gaping chasm in the Amazon. Brief dialogue exchanges encapsulate the characters well, giving a sense of urgency but never losing track of the series’ sense of adventure. Scrooge’s nephews pop up with clues, sometimes needing to be rescued, and, when I played, I could almost hear their voices in my head, even though it was only in text.

Lacey’s role as producer was also important in maintaining consistency for the characters. “The Disney universe is well-established, and its characters look a certain way, behave a certain way, and speak a certain way. It was my job to make sure we did not deviate from what had been established.”

Sticking to the core of the characters extended beyond dialog to characters’ behaviors as well. “We also needed to make sure that the content met Disney standards. For example [in another title] one licensee had Donald Duck clubbing baby seals! It was also important that the Disney characters weren’t killing things.” This led to creative gameplay choices, because, as Lacey explained, “The Disney game designs had to be more creative than simple point and shoot games. That’s how elements such as Scrooge’s pogo jump with his cane in DuckTales came about.” It also explains in part why none of the characters in the game die, but rather, get knocked off the screen.

One of the mysteries I and other fans have wondered is why Scrooge wears a red shirt in the game rather than the blue one from the cartoons. Lacey had the answer. “We changed it because Scrooge was not standing out very well against all the blue and dark backgrounds. The red suit made him pop.”

There were also additional edits, like changing the crosses Capcom originally put on coffins in the Transylvania stage. As Lacey explained, “It just did not seem appropriate, so we changed them to ‘RIP.’” In addition to that, “There was also originally an option for Scrooge to give up his fortune, but this seemed out of character, so we removed that.”

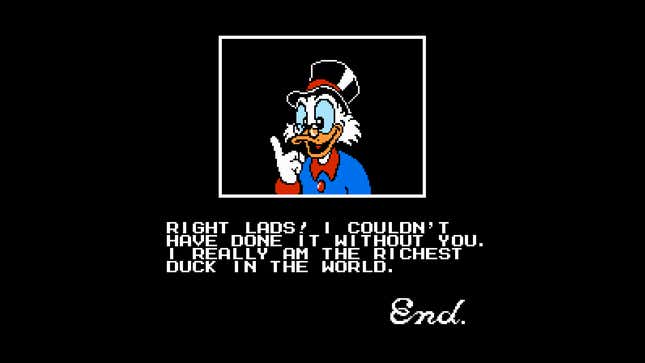

The most famous change Lacey made was in the ending. Initially, “Scrooge told his nephews: ‘There really is more important treasure than this. That is . . . Dream and Friends.’ It seemed so earnest and dramatic, I was so tempted to leave it as is, but I knew I couldn’t. So, I changed it to the more polished, but forgettable ‘Right, lads! I couldn’t have done it without you. I really am the richest duck in the world.’ I love that fans found out about the original ending. It was the better line!”

DuckTales for the NES released in North America in 1989, where it met with critical and financial success. It captured the spirit of the cartoons, whether it was warping through the mirrors of the ghost house in Transylvania or running away from a boulder in the Amazon and avoiding deadly spiked vines. The animated sprites were a joy, from the Mummy’s spinning after being hit, to Scrooge’s dazed eyes when he hits something too rigid for his cane, and even the way the cane crunches on a pogo jump. The music ranks among some of the best retro tunes of the era, with the Moon tune in particular being a classic. The finale of the game, which thrust Scrooge into a race against his two archvillains, Flintheart Glomgold and Magica De Spell, was exhilarating.

Tales of Daring

After the release of the NES game, Mullich produced a different take on the series in 1990’s DuckTales: Quest for Gold for Buena Vista Software, Disney’s first venture into game publishing. Mullich contracted Incredible Technologies, the company that made The Three Stooges for Cinemaware. “We determined early on that the objective of the game would be to earn more money than Scrooge McDuck’s arch enemy, Flintheart Glomgold, within 30 days. So, we established money collection as the player’s main goal, with a time limit as the goal’s obstacle.” They decided the game would primarily be a series of adventures, or mini-games, that featured different DuckTales characters and had either action or strategy mechanics. Mullich came up with the Launchpad McQuack flying minigame that connected all of the scenarios, as well as the stock market minigame for earning money. He also wrote the Junior Woodchuck Guide that served as the player manual and included the secret code copy protection mechanism, a table inside the manual for translating symbols into letters.

Mullich said, “One feature that DuckTales: The Quest For Gold had that the Capcom’s DuckTales game didn’t was voice-overs from the show’s characters. I worked with Disney Character Voices in producing the voice-over recordings, and it was my favorite part of development. They brought in [Minnie Mouse voice actress] Russi Taylor to record Huey, Dewey, and Louie. She was a lot of fun to work with!..We also worked with Terry McGovern, who was the voice of Launchpad McQuack. Terry was based in San Francisco, so we directed his voice-over sessions over the telephone while he was in a sound studio in the Bay Area. I learned a lot about producing voice-over sessions by working with the people at Disney Character Voices, and that experience helped me to produce much bigger voice-over sessions later on in my career for I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream and Vampire: The Masquerade — Bloodlines.”

Lacey went on to work on several other Disney titles, including the GameBoy port for DuckTales. “It was super easy, a clean and effortless port of the NES 8-bit version. I don’t recall making any significant revisions. Why mess with success? It was a great game.”

She also worked on another classic Capcom Disney game, Chip ‘n Dale: Rescue Rangers. “I always thought it was a cute and fun game, obviously more targeted toward a younger, less hardcore gamer market, but fun and pleasant to play. Like DuckTales, there’s a prototype of the game floating around, and it has been noted as having 31 lives in it. That could be just there for play testing purposes. If I recall correctly, Capcom gave me versions of the games for play testing that had either had unlimited lives or so many lives that it was the same as unlimited…This allowed me to relax and take my time going over all the details in my reviews. I would say that when I think of this project, I think of it as one of the most stress-free projects I worked on. I had a good time, just like the Rescue Rangers!”

Lacey said, “Connecting these days with the kids who played the games decades ago and remember them fondly is truly a great feeling.” Later, she sent me an email with a link to a YouTube video of a playthrough of Rescue Rangers, full of comments from gamers expressing how seeing the game evoked nostalgia and brought them to tears. “That’s very touching to me.”