A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blog about “Snake Eater,” the titular song in the 2004 video game masterpiece, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. In it, I gush about the song and how it is as responsible for the prestige of the game as anything else. Tucked into the final paragraph, I made an entreaty to the song’s performer, Cynthia Harrell, to get in contact with me. Her powerful vocals suffuse “Snake Eater” with such gravitas, elevating it from a simple song on a video game soundtrack to something that sees regular rotation in travelling video game orchestra performances and in people’s weddings. I wanted to hear from her, hear about her, and ask her if she knew what her song meant to people.

But I couldn’t find out anything about her.

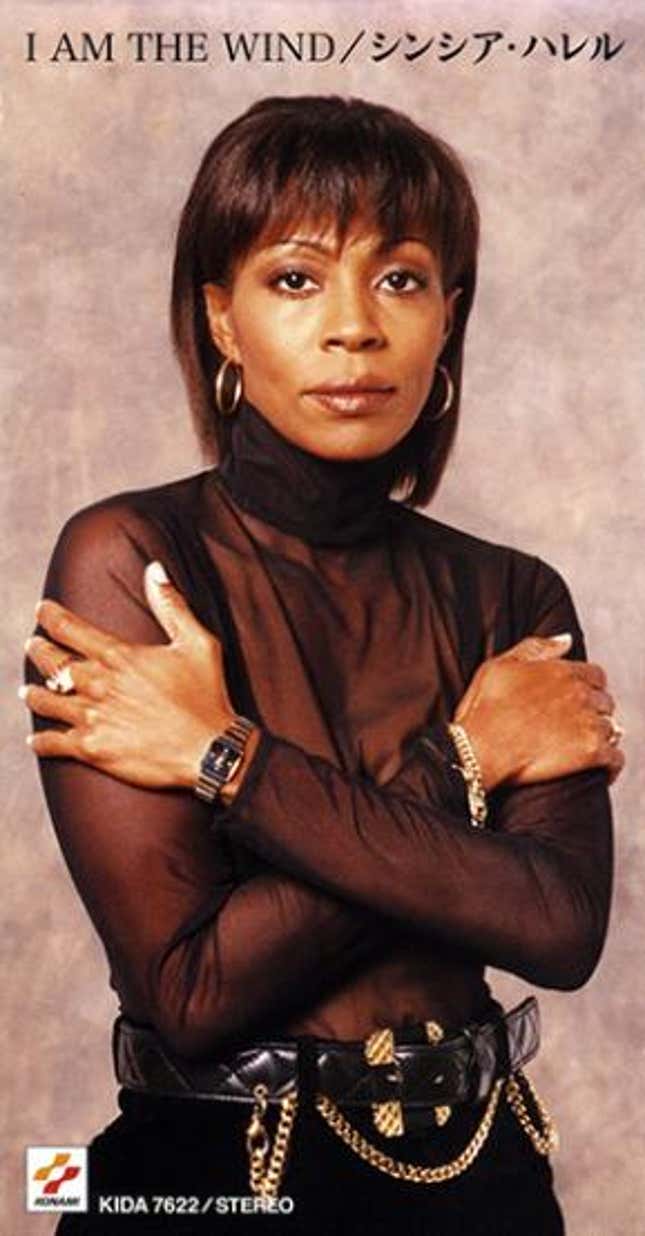

Google her name and the top results are her wiki pages for Metal Gear Solid 3 and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (wherein she’s credited for performing that game’s closing song, “I Am The Wind”). I couldn’t find any interviews. I didn’t know if she had gone on to do other video game work or not. In fact, one of the other top results from a “Cynthia Harrell” web search returns an r/videogamemysteries Reddit thread whose author posits she might be dead.

Concerned that this woman might be lost to me beyond the veil of death, I did my own research. I searched Facebook for surviving relatives mentioned in obituaries for Cynthias Harrell, cross referencing the locations of the many matching names I found against the location mentioned in the obits. Found a hit that way. My heart sank as I scrolled through the timeline of a person lamenting their lost mother. But then I realized this couldn’t be who I was looking for. This woman was white, and what little I did know about Cynthia Harrell is that she is a Black woman.

Frustrated by the dead ends, I made one last attempt that I realize now I should have started with: I searched Twitter. I found several hits for a Cynthia Harrell but only one with the picture of a Black woman who looked approximately like the woman on the cover of the Castlevania “I Am The Wind” single. Since this profile did not allow direct messages, I took a very public shot in the dark and @-ed her.

And she answered.

It took a week or so of stops and starts, buried under work and life, but I finally managed to speak to her. And y’all…Cynthia Harrell is awesome.

When we first started our phone conversation, what struck me was that Harrell sounded like one of my aunts. I was nervous before speaking to her. Nervous that she would find my sudden air-drop into her life intrusive. But she dismissed my worries with the soft, warm tenor of an older (but not old) Black auntie that instantly put me at ease.

“What have you done?” She asked me jovially. “You have brought back all kinds of memories. Jesus.”

The memory many of us have of Harrell’s work is this:

After defeating The End boss in Metal Gear Solid 3, the player needs to make the protagonist Naked Snake ascend a very tall ladder for three minutes. Nothing else happens for those three minutes. The game is quiet save the soft ping of Snake’s feet on the ladder’s rungs. In a game that’s part spy-thriller, part-gut wrenching family drama, it is a moment curiously devoid of any action or dialogue.

Then you hear Harrell’s unaccompanied voice slowly waft in as if blown on a breeze. It echoes faintly in the cavernous concrete shaft, slowly building in volume the higher Snake climbs before tapering off into quiet again when he reaches the top.

Without Harrell, that scene is just Snake climbing a ladder in silence, which wouldn’t be too out of place because Metal Gear games get weird like that.

With her though, that ladder scene becomes one of video games’ most memorable moments, all because of her voice.

Harrell’s own memories of her career and video games go much further back than that.

Cynthia Harrell started her professional career singing jingles for McDonald’s commercials at 10 years old. Like most Black performers, Harrell grew up singing in church. Her grandfather was a minister, she said, and most of her family in some form or another ended up in the entertainment industry. She had college aspirations and desired studying law, but the success of her singing career—and its time demands—diminished college’s appeal.

“I think at that time I wanted to go to Saint Xavier [University] and I was working while my friends were in school and it was like, ‘Wait a minute, I’m 18. I’m making my first $100,000 at 18. I’m staying here. And [I] just kept going and going and going and working and working and working with my aunts and my mother.”

A bout of the German measles during Harrell’s senior year in high school prevented her from joining her mother and aunts in California, where they were doing background vocals for Aretha Franklin’s hit “Giving Him Something He Can Feel.”

“My feelings are still hurt to this day,” she mused. Though she missed out on sangin’ with Miss ‘Retha, Harrell would get the chance to sing with another R&B legend. The group she was in with her mother and aunts, Kitty and The Haywoods, sang background vocals with Curtis Mayfield on his 1977 album Never Say You Can’t Survive.

Harrell worked in the music industry up until her retirement last year. She sang background vocals with Kitty and The Haywoods (sometimes known as the Kitty Haywood Singers), sang background vocals under her own name, managed music studios, and was even a background singer on the famous “Be Like Mike” Gatorade commercial.

In her vast body of work, she only has the two video game credits. One for Castlevania’s “I Am The Wind,” and the other, of course, is “Snake Eater.” Harrell got involved with those projects through her friendship with Konami’s longtime music producer Rika Muranaka. Muranaka, a Japanese native, studied music in Harrell’s native Chicago.

“I think it was in the ‘90s when I met Rika,” Harrell said. “She and I had worked together on some other things and we were friends.”

That friendship and casual working relationship led Muranaka to tap Harrell to sing “I Am The Wind,” the end credits theme for Castlevania: Symphony of the Night.

“She would tell me ‘I’m doing this game’ or whatever, and I would brush her off because I really wasn’t into hearing any of the gaming songs. [But] there were certain things she knew that my voice would fit with. And she would call me to do the demos. The next thing I knew, we were doing it as a final project.”

Several years later, in 2004, Muranaka once again asked her friend to sing for her, this time on Konami’s newest entry in the Metal Gear Solid series, Snake Eater.

“She asked me to sing. She was like, ‘Cyn, can you come sing this demo for me?’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, it’s fine.’ I think I went and sang it, and I knew it was something special about it. ‘Snake Eater,’ it was something different. A few months later, she called me and she said ‘King Records wants you to do the final version for the game.’ And I said okay, not even really thinking about it and went to do the final version. I show up to the studio—we were in Los Angeles—and I walk in and there’s this huge orchestra and that’s when I knew, this was a big deal.”

Harrell recorded the final cut of “Snake Eater” in two takes. After that, she went back to her job, Snake Eater continued development, and a few months later, Harrell’s phone rang again.

“The next thing I knew, everything just exploded with Metal Gear. It just exploded. [...] I got a call from King Records in Japan asking me if I could come there for the launch of the game.”

Though on crutches from a knee surgery, Harrell took the invitation from King Records—the label that released the first few Metal Gear soundtracks—and travelled to Japan to attend the release party for Snake Eater.

“The way they were treating me, you would have thought I was Barbra Streisand. I did MTV Japan, the local news, local radio, and it’s like, ‘Wait a minute, what’s going on here?’ These people knew the game, and they knew me from the game and I didn’t realize that anyone knew me or anything about me through that game.”

Harrell remembered performing her favorite song and the time she spent with Metal Gear’s creator Hideo Kojima.

“We were able to have dinner, which was awkward. He didn’t speak English at all, so we had to have an interpreter that sat with us in order for us to communicate. [...] I remember him thanking me for doing the game, and it was just regular conversation. I think it was Thanksgiving [in America] and they don’t have that [in Japan] so he was asking me about our tradition of Thanksgiving and things like that.”

Her star treatment in Japan carried over briefly back in the United states, but it seems sometimes that Harrell forgets how important her work on Snake Eater was to the gaming community at large. Occasionally though, she’ll receive a reminder.

“My goddaughter, told her boyfriend at the time when she was at Spelman and he was at Morehouse—that’s my godmother. And the next thing I knew I had fans on Morehouse’s campus and it’s like, ‘What in the world?’ not knowing that the game was as big as it was.”

Snake Eater won GameSpot’s “Best Story” award for 2004. IGN named it as one of the best video games of all time, the second best game for the PS2, and the best game in the Metal Gear franchise. Kotaku’s own Ian Walker counts November 2004 as one of the best months in video games ever in part because of Snake Eater’s release, and Polygon counts the ladder sequence—the moment when you hear “Snake Eater” for the first time during gameplay—as “the epitome of why [the] Metal Gear Solid series is so much more engrossing than the other gun-toting spy games it may at first resemble.”

A lot of that success has to do with the story Hideo Kojima wrote, and the way David Hayter and Lori Alan acted out their roles as Naked Snake and The Boss. But Cynthia Harrell’s performance of “Snake Eater” during the infamous long ladder climb is also part of the reason why we hold that game in such high regard.

Despite her connection to gaming history, Harrell demurred when I asked if she was a gamer. “Sort of. My son was the gamer, when he was growing up. And so I had to learn how to play Nintendo and Atari.”

Harrell played video games with her son mostly to help him out when things got difficult for him. But later on, she picked up a casual habit all her own.

“I’d find myself on days that I wasn’t working [playing] Zelda. Zelda was one of my favorite games. [...] When [my son] would go to school, I played Zelda. I’d play Mario.”

Harrell, by her own estimation, tended to play “kid” games. She likes Sonic the Hedgehog, The Cat in the Hat, and Super Mario Kart—games vastly different from the tactical espionage action the Metal Gear franchise is known for. So I was surprised and delighted to learn she frequently plays the game for which she is famous—on a PlayStation 2 that Konami gifted to her specifically for that purpose.

“When they sent the system to me and the game, I put it on and it’s like ‘okay, this doesn’t look like anything I’ll be able to do.’ [At first] It took me probably about six months to get through Metal Gear.”

Though she plays other games—she also has a fondness for the Batman Arkham series—Snake Eater is like her fall comfort game.

“Normally this time of year is when I start all over from the beginning. [...] If I feel like it, I will always go back to Metal Gear.”

Harrell retired in 2019 after a career that spanned 50 years. She does not sing professionally anymore, but will still sing in her house or while driving. She’s never appeared on the convention circuit, because “no one’s ever really asked.” She was dismayed to hear people thought she might be dead. She’s very much alive and would be amenable to an encore performance of “Snake Eater,” if asked.

Until now, outside of Harrell’s background vocals, commercial jingles, and her performance in “I Am The Wind” and “Snake Eater,” we have not had the chance to hear her voice—to hear this hidden figure of video game history tell her story. Finding her was a coincidence reinforced by a touch of shared family history. Like Harrell’s, my family is also from Chicago, and I too have family in the entertainment business, specifically jingle singing. When Harrell mentioned she did jingle work for McDonald’s, I idly wondered aloud if she could possibly know my cousin Jeff—who, in my family’s mythology—also sang jingles for McDonald’s.

“I know him very, very well. We’re good friends.”

I spent the majority of my time speaking to her trying to keep my jaw off my desk, because I was in awe. When she told me that she did indeed play video games, my face exploded in joy because it meant that I had found my own personal unicorn; a Black woman older than me who plays video games. More than that, she worked in video games, on not one but two of the most beloved games ever made—and I, through blind luck, was able to find her and speak to her, and share her story with everyone.

“What a thrill...”

(Updated 3/3/22 with new details)