In times of distress—and right now, I am constantly distressed, despite what manner of bullshit I post on Twitter—people seek out the things they need. Comfort, stability, understanding; we’ll scavenge until we can find a scrap of the emotion we need to feel more like ourselves. And I’ve found myself floating towards games that make me feel free of all this. Games that let me reshape the world in a way that feels as kind as reality is cruel. A way to define myself with any other facet of my identity than the ones overwhelming me right now. It’s an escape mechanism so timeworn and integral to my daily life that I could almost forget how it started.

You never really forget your first, however. I have told the story of my first video game hundreds of times.

I was six years old, and my Mom and grandparents pooled their money to buy my brother and me the hottest new-ish Christmas toy: the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. I had never even seen a video game before booting up Super Mario World, and it changed my life.

That SNES quickly became a stabilizing force in our childhood. After my father left, after my Mom fought to keep us off the streets, after I slowly realized what it meant to be Black and Indian and a child of divorce in a Canadian suburb, I needed something that made me feel like a regular kid, something that helped me turn my hyperactive brain away from the sadness and confusion around me. So I focused on video games like my life depended on it. I borrowed back issues of Nintendo Power and GamePro from the library until I had read them all. I memorized level layouts in the Mario World Player’s Guide until I could find my way to Star Road as easily as I walked to my babysitter’s house after school. I needed an escape, and I found one.

I have told the story of my first video game hundreds of times, and only recently have I considered that it’s been an apology, a shorthand way of valorizing my passions as coping tools. Another way to turn my love for my second-oldest hobby (I will die with a well-read book in my hand) into yet another parable about Black Sadness, the most enduring and popular lens through which the world demands to view Black Lives. When you only describe someone’s life with the language of trauma and suffering, you in turn curtail your own ability to comprehend them as capable—or worthy—of more than misery.

So it’s not an apology, it’s a part of me: Games have always been my first and favorite form of escapism, and some days (or years), my desire to escape is stronger than others.

But here’s the thing. Escapism is a trip, but it’s a round trip; it always drops you back off where you started.

Bloodborne

This is my first SoulsBorne game, and I finally get it. I went from skeptical outsider and passive consumer of memes to yet another person insisting that, no, you just need to give it 10 hours and then you’re locked in. But it’s true, or at least it was for me.

More than “getting gud” or rising to some mythical level of gamer skills, Bloodborne is about analysis. It’s the opposite of a power fantasy; the insights and understanding of the world and its enemies that you need to survive are things that you earn for yourself, not through inflated character stats or indulgent execution animations.

Getting better at Bloodborne handed me the tools to get better at my own life, because it gave me a running start of momentum and personal achievement. I began playing it when I needed a win in life, and figured that if I could at least get my shit together and beat a virtual werewolf/priest, I could tackle other challenges in turn. My wins in the game have directly affected my confidence in real life; no game has ever done that for me before.

But I hate it when I die.

Dying in Bloodborne is inevitable and instructional; it’s so expected that first-time players are essentially forced to lose and die in a fight within the game’s opening minutes. My avatar in the game is a Black man—or because of the game’s unique approach to character creation, more of a red-grey man—running around the City of Yharnam, a filthy homage to Victorian-era London filled with hordes of townspeople who will kill me on sight.

So when I die in Bloodborne, it’s often to the image of my character, the only Black man in the world, being torn to pieces by a screaming mob of white people. I can escape into the game’s rhythm and how it literally makes me master each encounter; I can feel support and hope when a friendly player hears the chime of my bell and helps me through a challenging area.

Then I am bludgeoned into silence by a crowd; my escape is over. But there’s always another game.

Civilization

I’ve been playing theCivilization games since high school, and when I want to watch an evening slip away between my fingers, I’ll boot up Civ V or VI, depending on which expansions and Civs I want to use. The games have a soothing quality, like reading a good book while listening to classical music. But they make me feel free because I can rewrite history, and try to graft kinder stories onto chapters that closed long ago.

I like to play as Civilizations that have often had their stories defined and truncated by colonization and genocide in the North American history books I had access to growing up; the Inca, the Zulu, the Kongolese, the Maya, the Nubians, the Cree. While all those cultures and people live on today (and some understandably take issue with their portrayal in these very games), it’s often with an asterisk, a reminder of the enduring impact of colonialism.

I go for Scientific and Cultural victories when I play. Partly because the war system in Civ stresses me out, and more because I just feel better when I pull them off. An underrated part of the modern entries in the franchise is their use of music; each Civilization has its own musical motif that hangs in the background as you play, gaining instrumental accompaniment and depth as you bring a Civ from the Ancient era to the Atomic age.

It’s transcendent to start a game to the sounds of folk music sung by South African A Capella group Legato and hear those same songs swell into a full orchestral arrangement as I send Zulu astronauts to a newly-discovered exoplanet (and land a Science Victory in the process). It makes me believe in everything again, especially because it almost always comes after a dozen hours of play.

It’s also so rare, because other Victories are more disruptive or efficient. I’ve lost more games of Civ than I’ve ever won, watching the stories I’m trying to rewrite fall once again to Domination and foreign influence. It’s an escape, but only to the point where I watch my society fall to the tanks and jets of Russia, Macedonia, or Germany. Then it’s just another sad story.

But there’s always another game.

Ape Out

SPOILERS: Spoilers for the ending of Ape Out below.

I bought Ape Out when it was released in February 2019, played through half of the first world, and moved on. It was Hotline Miami without guns, an exercise in style over substance. I picked it back up a few weeks ago, wanting to clear out space on my SD card, needing to look at something other than protests and eulogies.

I immediately learned two things: 1) I had been playing the game wrong (you don’t need to grab-and-hold enemies before throwing them, and you’ll die constantly if you play that slowly), and 2) Ape Out was a masterpiece.

It all clicked for me; the minimalist art style, the perfect marriage between action and sound, the crate-digging vibe of each level’s album art and liner notes, and the game’s commitment to showcasing jazz as the sonic equivalent of indescribable emotion. You are a gorilla fighting for freedom; why would we as humans be able to understand anything but the barest outline of that creature’s emotions?

I was not prepared for the ending, a moment so pure and surprising (yet also so logical) that it’s honestly worth it for you to buy the game, spend a couple of hours clearing it, and then come back to keep reading. I’ll wait.

Ape Out ends with the titular Ape escaping, once again. Not from a lab, or an office building, or a cargo ship like in previous levels, but from a zoo. And as you blaze your final trail of completely-justified havoc, the usual pinpoint-precise drums and snares become cluttered with other types of percussion unrelated to your movements. The animals you’re freeing from the zoo—the bears, the tigers, the turtles—are carving their own paths to salvation, and their sounds are adding to your own, in a roar of slams and crashes that is cathartic and chaotic. You aim your Ape for the treeline, break through a final wall of fencing, and disappear into the green.

And then, for the first and only time in the game, an entire jazz band starts playing behind the drums, with a blistering tenor saxophone solo cutting through the air like a scream as the credits roll and the song keeps playing for 10 uninterrupted minutes, if you allow it.

The song, “You’ve Got To Have Freedom” by Pharaoh Sanders—the world’s greatest tenor sax player—is lyricless, but its meaning hit me like a ton of bricks. In Ape Out, you play as an orange gorilla (the only orange-colored character in 99% of the game) that is not allowed to exist peacefully, and thus is spurred to violence to escape. You just want to be left alone, but if you stop for a second, you’ll be shot to death. You are captured and escape five separate times before those end credits, and the entire time, the drum beat is ceaselessly bearing you forward.

And you beat the game, you escape, and it explodes with sound and joy and depth that it wasn’t allowed to express before. I didn’t even know why, but I wept when I finished the game, composed myself, showed the ending to my wife while trying in vain to explain why this art project of a game about a gorilla was wrecking my shit so completely, and somewhere along the way I blurted out a single, shaky explanation: “I felt free.”

But there’s always another game.

Clubhouse Games

I bought Clubhouse Games because I knew the Nintendo DS original was a secret masterpiece, and my wife talks historic amounts of shit about her Connect Four skills that she had yet to actually demonstrate. (Update: She is very good at it.) But lately, I’ve been taking the Switch to bed and playing 15 minutes of Clubhouse on my own before passing out, usually early in the morning after hours of doomscrolling through Twitter, trying to bear witness to a moment in history.

I load up Clubhouse and I play some rounds with strangers. I play Gomoku and get my ass handed to me despite reading several volumes of Hikaru no Go in high school. I play Air Hockey to make immediate moral judgments of anyone who hovers their paddle near their goal like a coward.

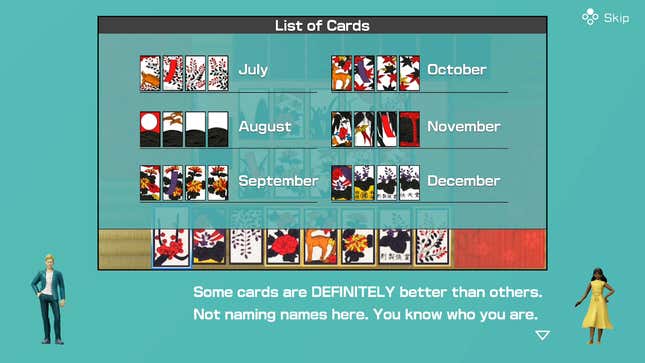

But mostly, I play Hanafuda, a traditional Japanese card game that I’ve always been interested in but never had the chance to learn. The rounds move quickly enough that, if I had a fun enough time with the anonymous player on the other side of our digital table, we can easily let one round string itself into half a dozen. There’s no one screaming into a headset, just the sound of cards slapping against a table, and occasionally a victorious shamisen song.

It strikes me that I’m playing a digital representation of a card game with roots dating back to the 17th century, if not earlier. It’s escapism within escapism that reaches across centuries to a time when ancestors I’ll never know the names of from a country I’ll never learn of walked the Earth.

You bring yourself (and everything you’re carrying) into every piece of art that you enter, and you always have to leave in the end. When I escape into a game, the reason for needing that escape always catches up with me.

But for a moment, for an hour, for a part of a day, certain games can make me feel free, and when that spell breaks, I’m grateful for the time away. I’m about to finish Bloodborne, I’ve already archived Ape Out, and I often don’t have the time for Civilization. Even though it’s an amazing deal, I’ll move on from Clubhouse at some point as well. It wouldn’t be much of an escape if I went to the same place every time.

But there’s always another game.

Mike Sholars is a freelance pop culture writer who believes that the best way to celebrate the things you love is to roast them relentlessly. He loves video games and anime. Follow him on Twitter @Sholarsenic.