Are you sitting down? I’ve got something to tell you—something that may shock you. Between the events of the various Donkey Kong games, the Kong family was involved in a bitter and vicious war. Among its many casualties, this war may have claimed the life of a classic Kong character, explaining his disappearance from all future games in the series.

This piece originally appeared 2/15/18. We’re bumping it today because it’s the 25th anniversary of Donkey Kong Country.

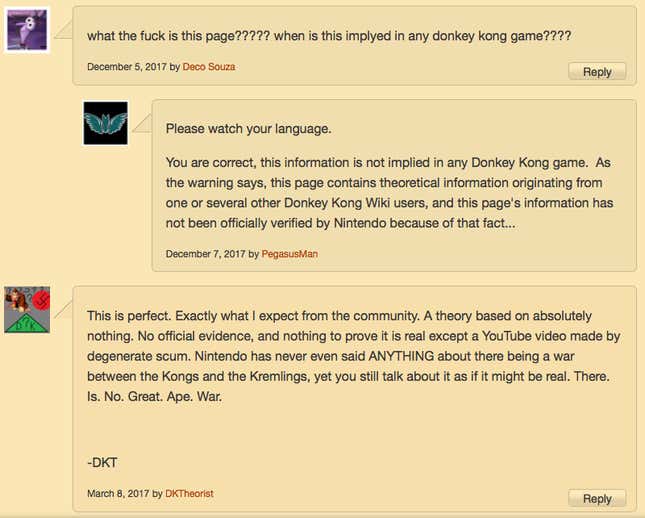

You won’t find mention of this Great Ape War in any of the Donkey Kong games, in their supplementary materials, or even in developer interviews. But none of that has stopped some fans from charting out complex histories of the war and its implications for the classic Nintendo franchise, in a fascinating example of how fandoms can run away with the smallest bits of narrative available.

The Classic Era

A series like Metroid has a clear chronology marked by a few major entries, and The Legend of Zelda series is complex but features the easy out of multiple universes. Donkey Kong is different—it’s Nintendo’s oldest major franchise and perhaps its least narratively-driven. Nonetheless, it does follow a timeline.

It seems clear that Donkey Kong Country for the SNES, is followed in-universe chronologically by DKC 2 & 3—after defeating King K. Rool in DKC, the crafty villain returns to kidnap Donkey Kong in the second, and then both Donkey Kong and Diddy Kong in the third. So far, so good. But things start to get a little trickier when we expand our scope past the entries on the SNES. Where do Donkey Kong Country Returns and Tropical Freeze fit in? How about the Donkey Kong Land series on the Game Boy? The spinoffs like Diddy Kong Racing and Donkey Kong Jungle Beat? The original arcade series?

Well, the Donkey Kong Wikia claims that the first chronological entry in the series is actually Circus, a 1984 Game & Watch title in which Donkey Kong must perform as a captive ape for Mario’s amusement. This makes sense given the little-known narrative of Donkey Kong (1981) was confirmed by Shigeru Miyamoto himself in a 2016 interview: “Mario kept Donkey Kong locked up, so he escaped with his girlfriend.” Thus, the original Donkey Kong arcade game gets recontextualized. Instead of kidnapping Pauline (or “Lady”) for seemingly no reason, Donkey Kong is seeking vengeance against Mario for his wrongful imprisonment. It’s also possible that Circus comes after the original game, a kind of interquel between Donkey Kong and Donkey Kong Jr. that provides context on Mario’s treatment of the elder Kong after defeating him the first time.

Regardless, at some point Mario defeats and imprisons Donkey Kong—we know this much from the premise of Donkey Kong Jr. (1982), in which Mario makes his first and to this day only appearance as a villain. Taking on the role of Donkey Kong’s son Jr., the player must free DK from Mario’s clutches and ultimately kill Mario, raising some serious questions about the plumber’s mortality.

After this, in Donkey Kong 3, Donkey Kong fought an exterminator. Nobody really cares about that one.

Moving to the country, gonna eat a lot of bananas

Sometime after the events of the original arcade series, Donkey Kong moves from Big Ape City to the wilds of Donkey Kong Island, the eponymous setting of the Donkey Kong Country series.

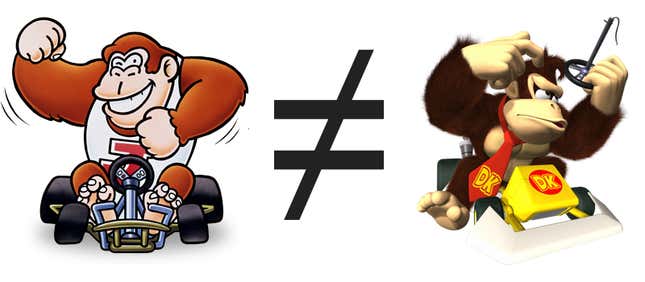

Here things get a little confusing. It seems clear that the playable Donkey Kong is not the original from the arcade games. But is Cranky his father or grandfather? Some Rare sources claim the former, but Donkey Kong Country’s instruction manual contradicts this. More recent Nintendo games such as Super Smash Brothers Brawl seem to have cemented Cranky’s status as modern Donkey Kong’s grandfather.

But if Cranky is Donkey Kong’s grandfather, this presents a problem for the Kong family history. What became of Donkey Kong Jr.? In Rare’s original pitch for DKC, the monkey character that became Diddy Kong was originally intended to be an updated version of DK Jr. Rare was presented with a choice: use DK Jr.’s original, ape appearance or rename the new character. In a decision that would forever change Donkey Kong history, Rare chose the latter, thus leaving DK Jr. out of the DKC series and positioning Diddy Kong as DK’s nephew.

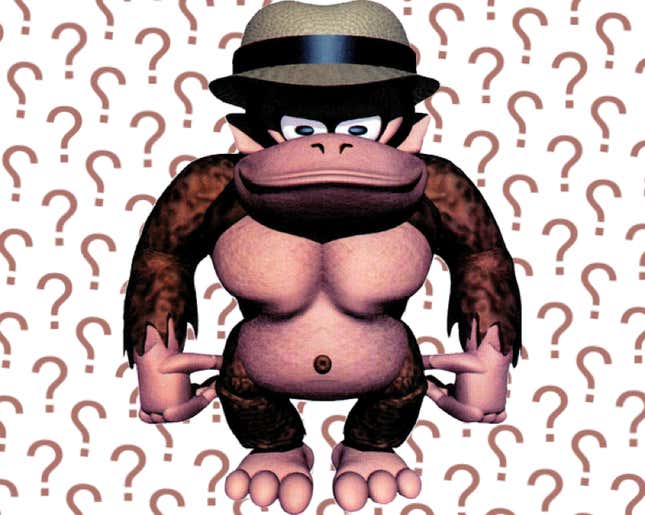

While DK Jr. is conspicuously absent from the Country games, early Nintendo Power coverage of Donkey Kong Land—the Game Boy adaptation of the DKC series—suggests he was not entirely forgotten. In a pre-release article from issue 69 (1995) of the magazine, several renders of characters appear who would not be included in the final game. One of these characters is a Kong sporting a fedora. We have no information on who this character is, but we can speculate based on his appearance.

Aside from being the sartorial equivalent of a condescending “m’lady”, the fedora can be used to denote a kind of classic American fatherhood—think Finn and Jake’s dad in Adventure Time. Is it possible, then, that this Kong was meant to be the lost Donkey Kong Jr.? Maybe, or maybe not. But regardless, what happened to Donkey Kong Jr.? If he isn’t the modern tie-wearing Donkey Kong, then where did he go?

Say it with me: Great. Ape. War.

The Great Ape War

The Donkey Kong Wikia describes the Great Ape War as a conflict between the Kongs and the Kremlings. So far so good—the Kremlings are the major antagonists throughout the Donkey Kong Country series right up until Donkey Kong Country Returns. Furthermore, the story set out in the DKC manual opens with Diddy watching over DK’s banana horde to keep them safe from the Kremlings, so it’s safe to say the DK crew had tangled with the scaly menace prior to the events of that game.

Conflict is one thing—a war, though? That’s another banana altogether. The evidence for the Great Ape War is scant, so it’s easy to dismiss it as a fan theory made from whole cloth. However, it explains a great many mysteries of the Donkey Kong world, so it’s worth considering.

What mysteries, you may ask? Well, there’s the aforementioned disappearance of DK Jr., for one. But what about the Manky and Minkey Kongs? Described as “Kong rejects” in the DKC manual, they appear as the only primate foes in the series. What were they rejected for? Perhaps they defected from the Kong family in an earlier conflict with the Kremlings?

And why do so many characters wear military gear in the Donkey Kong series? Kind of weird for a series about anthropomorphic animals who mostly don’t wear clothes set on a tropical island, no?

What else could explain all of these confusing phenomena except for the existence of a war between ape and reptile prior to the events of the Donkey Kong Country series? Let me lay out one scenario for you.

War breaks out on Donkey Kong Island. Cranky Kong is either too old to fight or else was psychologically scarred by his defeats at the hands of Mario and later Stanley the Bugman during the events of the DK arcade series. Modern Donkey Kong is likely too young to do battle. So DK Jr. leaves his son with his unknown wife and heads out to repel the Kremling forces.

But alas—and perhaps at the hands of the Manky betrayers—fans theorize that DK Jr. was defeated in combat. Was he killed? Did he escape by going into hiding as the aforementioned Fedora Kong? Or, as one YouTuber suggests, did he perhaps end up as a POW, forced to fight the enemies of the Smithy Gang in Super Mario RPG as one of the many Chained Kongs encountered in that game?

If this last possibility is the true story, then it would be a grimly ironic end for DK Jr.—having once rescued his father from imprisonment by Mario, he finally met his end in chains at the hands of the very same plumber.

We may never know what happened to DK Jr. But life goes on. After the war’s conclusion, King K. Rool marshalled the Kremling forces once more and instigated an all-out assault on the Kongs with the explicit intention of denying them their food source and thus starving them to death so that he could occupy Donkey Kong’s home. This is the conflict that spans the DKC series—K. Rool first steals DK’s bananas, then kidnaps him, then kidnaps him and his nephew, and then finally attempts to blow up the entire island in Donkey Kong 64.

It’s possible that this conflict was a deliberate reference to the real-life Banana Wars, in which the militarized occupying force of the United States sought to subject tropical countries and exploit them for its own enrichment. Sounds a little like the Kremlings—an industrialized, belligerent group of conquerors who invade Donkey Kong Island to steal the Kongs’ prized bananas—doesn’t it?

But maybe it isn’t just a simple reference. Maybe the presence of modern military equipment—and even crashed planes in Tropical Freeze, which could hardly be the work of the primitive Snowmad foes of that game—suggests that the Donkey Kong Country games take place in the real world, alongside actual historical human wars. What’s the alternative, that military hardware just fell out of the sky? Get real. Whether or not there was a Great Ape War, there are definitely humans fighting brutal wars of occupation alongside the colorful adventures of the DK crew in the Donkey Kong universe.

The present day

That brings us up to the present day, in which Donkey Kong shares a universe with Mario and the ancient conflicts between the Kong family and the plumber have mostly been put to rest. In the Mario vs. Donkey Kong series, Donkey Kong and Pauline even become friends. This sets the stage for Super Mario Odyssey, in which Pauline is the mayor of New Donk City—possibly the same Big Ape City from the original Donkey Kong.

The events of that game are now so distant that they are no longer horrific but part of a festival reenacting Mario’s triumph. This, combined with the fact of New Donk City’s name and many references to the Kong family and friends suggests that the beef has been squashed and plumber and Kong now live in peace. What rivalries remain are expressed chiefly through the gentlemanly sports of tennis, board games, and kart racing.

Making sense of game theories

Why would anyone try to make sense of the Donkey Kong Country world, a series which is almost completely devoid of narrative? And why do videos on “Game Theories” claiming to explain secret narratives behind relatively plotless videogames get millions of views? The easy answer is that it’s all for a laugh. And sure, the inherent absurdity of charting out the family trees and timeline of the Donkey Kong series is part of what’s going on here, but I don’t think it’s the whole story. To really understand what’s going on, we need to talk about the medium that these conversations take place on: the internet.

Back in the 90s when internet access was scarce, the schoolyard currency of choice for gamers was codes and secrets. If you knew how to turn on the blood in Mortal Kombat, or access any level in Sonic 2, you were hot shit. And the only way you’d learn about these codes was through game magazines. Maybe you occasionally got your parents to buy one for you, maybe you browsed them at the library—or maybe you were one of the lucky bastards who had a subscription. Magazines were the means by which secret information entered the ecosystem, to be shared or withheld as dictated by the unfathomable rules of preteen culture.

Even when the internet entered the picture, things didn’t change much. The early internet was so chaotic, and users’ online literacy was so limited, that authoritative sources were often indistinguishable from someone’s Geocities site claiming to have exclusive information on the star statue in Mario 64. If anything, this early period of mass access to the internet confused the situation even further by adding external sources of rumours into the mix. This was the era of “Pikablu”, in which everyone and her brother fervently believed that Mew was waiting for us under the truck next to the S.S. Anne in Pokemon Red and Blue.

As the internet became an everyday fact of life rather than an exciting novelty, things firmed up, took on a more solid quality. New bastions of authority were formed to replace the game magazines: sites like GameFAQs featured peer-reviewed cheats sections, which cut down on rumours and flagrant lies. Simultaneously, ROM hacking became more accessible and it became possible to conclusively say whether or not a certain claim was true. No, we learned, there is no such thing as Pikablu or the Pokegods—”Pikablu” was in fact the relatively common Marill, from the then-upcoming Gold and Silver titles.

The final nail in the coffin of the cheat rumour economy was achievements. When videogames moved online en masse, console creators beginning with Microsoft pushed the concept of displaying your victories to other players. These accomplishments, of course, would be meaningless if achieved through cheating—and so codes all but disappeared.

Today, achievements are ubiquitous, games can be easily pulled apart at the level of code by players to reveal their secrets, and reliable Japanese-to-English translations for all news of major titles are easy to come by—making it trivial to check the legitimacy of any claim about a released game’s actual content. But the human mind is not content to sit back and enjoy this state of affairs. If the code of games has been thoroughly mapped and catalogued, then the mind has found something more ephemeral to ponder: narrative.

Let me illustrate. If you tell me that Luigi is in Super Mario 64, I can tell you that you are lying or misinformed. The conversation is over. But if instead, you tell me that Super Mario Brothers 3 is a stage performance within the Mario universe, I can offer no such rebuttal. I might argue against your claim, or I might consider its implications. But short of the rare Word of God, nobody can finally arbitrate this claim. The conversation can continue forever.

Which brings us back to the Donkey Kong timeline. Is trying to piece together an in-universe timeline for a series like this silly? Absolutely. Are there simple out-of-fiction reasons for all of the quirks of the Donkey Kong universe? Definitely. Is the Great Ape War merely the deranged invention of a forgotten editor on a second-rate fan Wiki, now mined for YouTube videos? Possibly. But none of these things matter.

In a media landscape dominated by crossover superhero movies and post-Lost TV shows that present themselves as puzzles, and in which the code of videogames is no longer impenetrable and mysterious, it makes perfect sense that fans would dive into the stories of games. And the more ill-defined the plot of a series, the more room there is to play and explore. So while we may never see the Great Ape War played out on a Nintendo platform, and Donkey Kong Jr. may be lost to history, these events and characters will continue to live on in fandoms.

merritt k hosts the podcasts Woodland Secrets and dadfeelings, and can be found on Twitter at @merrittk.