Your boss just pulled you into another surprise meeting. You’ve got a case of the Mondays. And your raise got rejected. Why not leave it all behind and roll the dice on a new career in video games?

Aside from the design, art, and programming jobs we often think of, the “games industry” includes everything from grips setting up motion capture studios to psychologists studying microtransactions. There are endless reasons to take the risk of quitting your job, and just as many reasons to tough it out and stay the safe course. The tricky part is figuring out which apply to you. Regardless of if you can write a single line of code, or if you have a hundred or a thousand YouTube subscribers, you first need to look at what you’ll be leaving behind.

First, Ask Yourself: Should You Quit?

Tom Sennett is a game developer who quit his job to live in a van and make games as he traveled the country. Who better to advise on this topic than the creator of a game called “Hate Your Job”?

“First, be certain the job is what you hate,” he told Kotaku. “I didn’t actually hate the job I quit. I hated living in New York, and having to go be in an office at certain hours, and burning all my money on living expenses. The job wasn’t perfect, but it was definitely one of the best I’ve had and had me on a great career path. But I realized my overall life situation was killing me, and I had to do something about it. So I ended up blowing up everything.”

Even if you’re certain you want to quit, the obvious concern is the cost of living once you do. Have a family? Probably can’t live in a van. Going from six figure salary to a QA tester? You might have to live in a van. And then there’s health insurance to worry about. It’s okay, because nothing could be as bad as dealing with your eight bosses, right?

The problem is, depending on exactly what you want to do, making games may be just as grueling as your current job. Eighty hour weeks, cancelled projects and routine layoffs are, sadly, some of the hallmarks of game development.

So what exactly is it that you want to do? If the first question is about your current situation, then the second question is about where you’ll go next.

Do You Need To Quit?

The answer largely depends on what kind of games you want to make. Nobody makes a game like Call of Duty on their own. At the other end of the spectrum, nobody gets a 401k and health insurance for making Skyrim mods. And of course, many people who work on larger games never come close to a line of code.

Do you want to play games all day? Becoming a developer often guarantees you’ll be too busy to sink 50 hours into The Witcher. You could try being a YouTuber or streamer, but that comes with its own risks. In other words, what exactly does game development offer that you don’t have now? Freedom, excitement, community, money? Creative or technical challenges?

If you don’t know the answer to those questions, then having a big savings account or tickets to GDC isn’t going to help you.

Let’s look at a few of the many different paths you could take:

The Visionary

“I’ve got a great idea!” you might think. “It’s an augmented-reality MMO with a persistent world and RPG elements. It’ll be f2p, and we’ll make money through microtransactions. I’ll get artists to work for credit and revenue share only.”

If you have a big dream you want to put into the world, you can absolutely do that. There are endless resources to get you started. Right now, though, our concern isn’t if your game idea is too big to make, but if it’s too big to make while keeping a roof over your head.

Sure, your actual idea is more realistic than the example I gave. But even the most realistic game projects fail in a market as saturated as this. A quick search for “indie game postmortem” brings up thousands of results, many of which are stories of passion and hard work leading to commercial success. Those stories make for great blog posts. There are fewer written by dejected developers dealing with debt. While conference talks about failed projects get plenty of accolades for bravery, not everyone wants to revisit their stressful failures.

One frustrated developer recently wrote about trying to sell his first game after spending five years and all their money developing it. His conclusion? “If you’re someone seriously considering going into indie dev right now, my honest advice is don’t.”

Of course, that’s an extreme view. Most advice is to keep your first game small and not expect much in the way of sales. Don’t get too discouraged: a small game can still become a big hit, even if you didn’t plan for it.

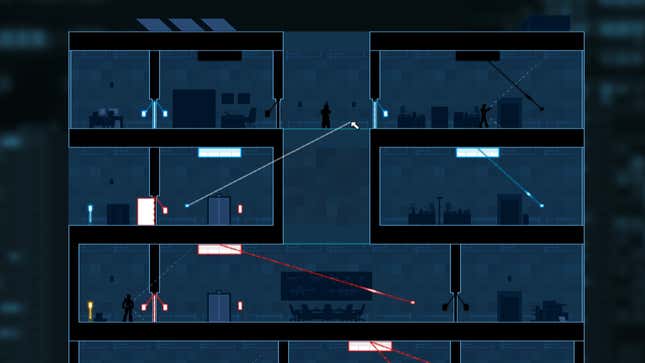

Tom Francis was working as an editor at PC Gamer UK when he learned about GameMaker. He decided to learn the software by making a small game in his free time, and using that to apply for jobs at development companies. Then, the game became an unexpected hit.

“So, I quit my job,” he wrote on his website back in 2013 “In fact, I think I have quit jobs, as a concept. I started Gunpoint as an audition piece to get myself a position at a developer, but designing it has been so creatively satisfying that I no longer want one, and so commercially successful that I no longer need one.”

Regardless of the size of your game, there are alternatives to betting the farm on one project, and the simplest one is hanging on to a steady source of income until you have a project that’s so good you absolutely need to spend every waking hour on it. As Threes illustrator Greg Wohlwend writes, “If you’re excited to work on your game when you get home, you love it and love working on it, why get married?”

The Hobbyist

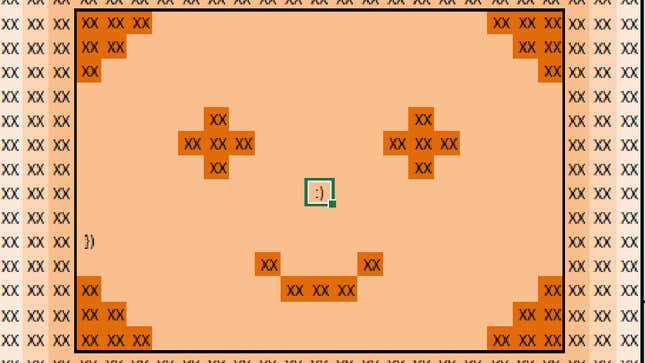

One great example of someone who made the best of balancing their old job with game development is Cary Walkin, who made Arena.Xlsm, a turn-based RPG in Excel while still working as an accountant. He spent his time in high school creating mods and custom Counter-Strike levels, but when it came time to find a job, he had to make a choice: “Ultimately, when deciding on careers at that age, I realized that jobs in the game industry were rare,” he told Kotaku, “so I took a break from game development and pursued a CPA.”

After Arena.xlsm was released, it spread around the internet and made a big change in Walkin’s life: “Releasing Arena.Xlsm completely changed my career path, and I have no idea what my career would look like had I not released Arena.Xlsm. Launching the game allowed me to go into the games industry full-time as a Games Consultant. I founded a games consultancy firm and an indie game studio, Walkin Games.”

Even then, the grind of the game industry caught up. He took a more traditional job in the software industry for a better work-life balance, but still works on games. “To balance game development as a hobby, I can do game development tasks for my game projects and for clients on evenings and weekends,” he said. “I’ve also been able to travel to game conferences and universities as a speaker on game development topics such as: ‘Game Design with Big Data,’ ‘Advanced Spreadsheet Skills for Game Designers,’ and ‘Business Skills for Indie Game Developers’.”

Because he likes a challenge, he then got Arena.xlsm greenlit on Steam and is working on integrating the Steamworks features into Excel. (He’s got trading cards enabled.) So not only can your day job keep putting food on the table, but it can also inspire you to create something more unique than you could have come up with while working alone at home.

Worst case scenario: it’ll definitely make your resume stand out when you’re looking for your next job.

The Jack-of-All-Trades

Offices don’t run themselves, and programmers don’t have time to wrangle voice actors or write contracts. There’s plenty of advice on how to become a game designer or programmer, but a crucial part of releasing games is done by the people who never write any code. Someone needs to research conspiracy theories for Assassin’s Creed, record the sounds of a billion guns for Call of Duty, or answer xxxSn1peMast3rxxx’s tweet about preorder bonuses.

At Naughty Dog, developers of the Uncharted series, operations specialists make sure that the developers can keep developing.

“Naughty Dog is very, very busy and my department wears many hats,” one of Naughty Dog’s operations specialist told Kotaku. “On a typical day, my stuff would include tracking people’s whereabouts (Are they out sick? Vacation?), payroll, fielding questions about the company/benefits/events (I also work in an HR capacity), interfacing with new employees, helping create documents for the studio, handling sensitive backend documents for employees, worrying about people’s travel, expenses, planning events, sending company emails, and keeping the studio in working order. Among a million other random things that can pop up or little fires we need to handle ASAP, I would mostly say it is taking care of the employees and running the studio (our house) while they are busy creating the game.”

On top of the general-purpose Operations jobs that need doing, Naughty Dog has many more non-programming staffers running around behind the scenes. “QA is very important,” the specialist, who prefers to remain anonymous behind-the-scenes, said. “Producers, though we don’t have any true ones, help keep people on track. We have two amazing girls that work in that sort of way here (scheduling our internal teams and wrangling our actors). We have the localization people that make sure the subtitles, languages, and things are on point. We have people that manage our external outsourcing teams.”

CCP Games, creators of EVE Online, famously employ economists to study the complexities of the universe they’ve created. Blizzard and Valve need video editors to create those beloved YouTube shorts showing off their characters. If you’ve ever been to PAX, you’ll know that even basic customer service skills can turn into a job showing off a new game to thousands of fans.

The Side Job

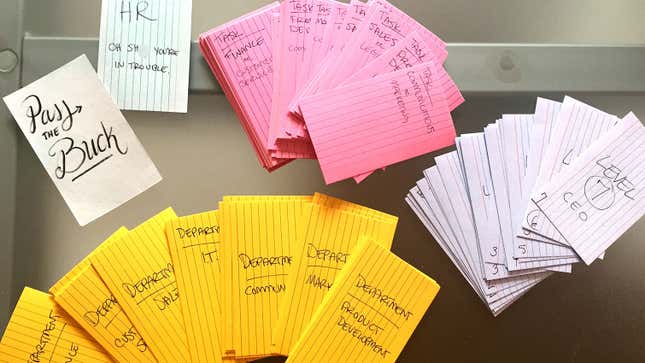

Carol Mertz always loved games, but never actually considered making them. After studying animation and interactive media in college, she co-founded a web design studio, The Rampant, which took off and became her main job. Eventually, her friends helped turn her interest in playing games into a hobby developing them. That side project became part of The Rampant, but even with the support of a stable company, releasing games is difficult.

“Even though we started making games as Happy Badger Studio in 2011, we never did make any money on the games we launched,” Mertz told Kotaku. “Making money is easily one of the hardest parts of making games. We came in knowing nothing about what we were doing, and we didn’t have access to mentors or peers who could help give us insight about process, polish, publishing, and promotion. We would make games, and they would flop into the ether and that would be that. The local dev community has grown and matured a lot in the last few years (which has helped us immensely), and while we know a lot more about making and promoting games, it’s still a huge challenge.”

Since then, the company has focused more on games and interactive experiences and is releasing their first console game, SmuggleCraft, on PS4. Meanwhile, Mertz has turned her experience running a company into a job doing business development for a game studio. Even though she’s now working in the games industry, she still makes her own games as a hobby, because what you want to make isn’t always the same as what makes money.

“I don’t really have an idea for how I want my solo projects to evolve yet,” she said. “I’ve published a card game, posted a couple expressive microgames on itch and have piles of prototypes and game ideas waiting in the wings. With the personal projects, I struggle to find a balance between just wanting people to be able to experience the games I make, and wanting my games to be a reasonable source of secondary income. I guess that’s the balance between keeping it a personal hobby and making it a professional focus. As of now, my personal work remains a hobby that takes a backseat to my full-time endeavors.”

The Freelancer

Aside from organizing a game jam on a cross-country train, Adriel Wallick is probably best known for leaving a job building satellites to make games for a living. She also spent a year traveling the world and living on couches while making a game every week. Before running away to make games, Adriel went to school for Electrical Engineering and then got a job at Lockheed Martin working on weather satellites. Later, she moved to writing software to process data from those same satellites, and around that time, she learned that there were other, non-satellite based jobs out there.

“It was about a year into that job where I discovered indie game development and realized that I could make games and turn that into a career,” she told Kotaku. “I had always loved games, and would have liked to have found a career making games, but it was something that I had brushed off as ‘not a real career’ that I could have. So, discovering indie game development was definitely a big shift in my thinking and desires and was the first time I had really felt a desire for a specific line of work.”

After getting acquainted with the games scene in Boston by attending events and conventions, Wallick was offered a job at Firehose games working on Rock Band Blitz. After that, she took a job at another studio making games and museum installations. Full time game developer with steady work! Dream achieved, right?

While getting to work on games at all is great for many people, others are more interested in the freedom of being self-employed. That’s what was on Wallick’s mind when ssome personal problems left her ready for a change. With about six months of expenses in her savings account, she let her lease expire, hopped on a train, and started traveling around the world. She’s currently paying the bills by taking contract programming work in between her own projects, a model she learned while her parents were living on a sailboat. “During their time sailing, they’d meet people from all over the world,” she said. “I was always fascinated by the people that they would meet who were in the position where they’d sail for as long as they could [afford to], and then pick up a job to replenish their finances. The jobs themselves were never important and were only necessary to fuel the adventure.”

As exciting as that lifestyle is, it requires very careful planning and management of your money and schedule to not get stuck without income when you need to pay rent. It also relies on having a good reputation, not only for your programming/art/etc. skills, but also your ability to deliver as a freelancer. Building up a network of clients and a good portfolio is critical before trying to make that particular leap.

What To Do Next

It’s time for the hard part: can you afford to quit?

General career advice is simple: “Don’t quit until you have a better offer.” It’s easier to get a job when you already have one, and you don’t need the additional stress of unemployment. Wise as that advice may be, entirely switching careers or gambling on making a hit game is far from a simple situation. What you need are numbers and a plan.

Check Your “Now” Numbers

If you suddenly had no job, could you pay next month’s rent? How about six months’ worth? You probably have an idea of how much you pay each month in bills, but the question you need to ask yourself is how much does it cost to maintain your lifestyle? Add up your rent, utilities, loan payments, phone and other recurring bills. Then add in drinks after work, doctor’s visits, Amazon Prime, Steam sales, parking tickets, and so on ad infinitum. It’s easy to see how six months of rent payments can only add up to two months of actual expenses, and that’s a realization you want to have while you’re still getting a steady paycheck.

When Adriel Wallick went from a company worth $75 billion to a small studio making a downloadable game, she not only took a large pay cut but also lost out on a retirement plan with company matching and health insurance. That was possible because she had a significant other with a good job, and because she had saved up money and established a frugal lifestyle before taking the lower-paying job. It’s much easier to get used to living on home cooking and ramen noodles when you can still afford an occasional take-out order after a bad day.

If you don’t have the slightest idea where to start, budgeting tools will help you quickly get an idea of what you really need financially. Mint and Personal Capital are both free, and they’ll automatically connect to your bank and credit cards to show you where your money has been going. Once you know that, you can figure out how long your savings will last.

Even if you’re living rent-free with family, you still need these numbers. Most parents won’t be thrilled if you quit a well-paying job to take a chance on video games with no plan, and if it’s been a while, they may just be tired of you never doing the laundry anyway. Six months of living at home might be great for your budget, but you should have a plan in case the YouTube channel doesn’t take off.

On the other end of the spectrum, if you’ve been working for years or decades and thinking “what have I been doing with my life,” you should probably check on that 401k you signed up for years ago (hopefully) and then forgot about. Do that before you take a $30k job for the free games and swag.

Figure Out Your “Later” Numbers

After you’ve narrowed down what you want to do and how much money you need, figure out if they match up. Gamasutra surveyed 4,000 game developers in 2013 about their salaries. Here are the average salaries they found:

- Business and management: $101,572

- Audio professionals: $95,682

- Programmers: $93,251

- Artists and animators: $74,349

- Producers: $82,286

- Game designers: $73,864

- Quality Assurance: $54,833

And for indies, as you might expect, the numbers are lower:

Non-salaried solo independent game developers made an average of $11,812 (down 49 percent year-on-year) last year, while individual members of an indie team made an average of $50,833 (up 161 percent). (These averages do not take into account indies who made less than $10,000, or over $200,000.)

These numbers are good for getting an idea of what to expect, but they’re a few years old and only a small sample of the thousands of people working in games. They also don’t take into account benefits like health insurance or retirement plans (or lack of them). When doing your own research, the employer review site Glassdoor is a good place to get a better idea of what to expect for a specific job, company, or area.

If you’re going it on your own, either by making your own game or starting a company, you’ll need to also get an idea of what kind of expenses you’ll run into while doing that. Those costs will change wildly depending on what you’re trying to do and your personal situation, so even after a ton of research, your estimates won’t be perfect.

For one example, Tabby Rose made the jump from Biomedical Communications to running her own company in stages. First, she did freelance web design work on the side with her husband, Jeff. Next, they saved up about $10,000 and used that to incorporate their business, get an office space and hire two employees. Then they submitted a jam game for a Canadian government grant and received $98,000 to develop it into a product. So where did all that money get them?

“It’s been a year and a half since we got that grant, and it’s been pretty much spent out at this point, so we ran a Kickstarter in the spring to top up our costs, which successfully raised an additional $27,500. It may all seem like a lot of money, but when you consider that we are four full time developers, plus about six contractors doing various things for the project, that money goes really fast.”

Luckily, their company is structured so that they can still take on client work to fill in any funding gaps they run into.

Know What The Job You Want Will Get You

There are a ton of different ways to work in the games industry, but in terms of finances, they all can be grouped into a few categories:

- Steady jobs that pay enough to support your lifestyle

If what you want to do falls into this first group, fantastic! Save up a little buffer money and start applying to jobs. Remember, the job you want may not be in the same place that you’re currently living, so be prepared to spend money to move (and be prepared to move your life to another city).

If you’re looking for a job at an established studio, start by looking nearby. Gamedevmap lists game studios around the world, but don’t rely on a single resource to have every studio. Twitter and Facebook often have announcements about job openings, so make sure you’re following any companies you want to work for. Industry groups like the IGDA, NYU Game Center, and Gamasutra often announce when companies are hiring, or even hold their own career fairs. Look for schools or organizations in your area to find out if you have any similar local events.

- Steady jobs that don’t pay quite as much as you’d like

For this second group, you need to start looking at those lifestyle numbers and seeing what you can afford to change. If all your money is going to Ubers and buying take-out, it might be easy to cut expenses. Buy a bike and learn to cook. They’re both great for your health. Ideally you’ll develop those habits before jumping into a lower paying job, because while being frugal can help you gain a lot of freedom, it’s a lot more stressful when you’re doing it out of necessity.

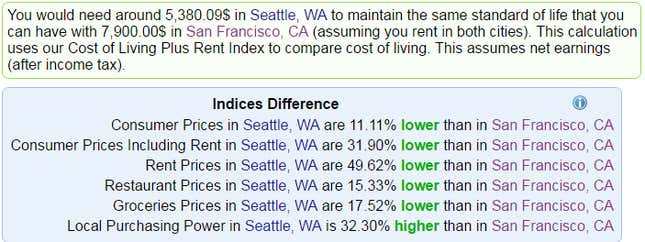

If you’re living in San Francisco and paying $3,000/month for rent, it’s probably going to be tough to cut expenses while staying where you are. Cost of living indexes can be helpful, but make sure to find one that shows you details. For example, high property taxes and gas prices might raise an overall index, but wouldn’t affect you if you’re renting and biking everywhere.

- Intermittent work from contracts/grants/self-employment

Almost any kind of freelance work involves a lot of word-of-mouth to succeed. You could get one big contract and be fine for a few months. Once the contract is over, if you don’t have another one lined up, you’ll be far more stressed than when you were at your day job. It’s never too soon to start going to events and meeting people, and having a portfolio of side projects can be the difference between getting your first contract or missing out. Things like GameDevDrinkUp where you can meet people over beers, or classes and events are good for getting started. Community groups like reddit’s /r/GameDevClassifieds are a good place to look for indie jobs that may be small enough to do on the side.

Also, did you know that some self-employed people have to pay taxes quarterly? If your plan only leaves you a small margin for error, details like that can be what cause it to blow up in your face. Make sure you research everything you’ll be getting into, and talk to an accountant if you’re starting a business.

If you want to go it alone and make your own game, community is still important. From answering technical questions on twitter to marketing help and job offers, most successful indies rely on the community to some degree. Even if your game is already made, events like NYU’s Playtest can help you find out if your game is actually working the way you want it to.

Tabby Rose also has this reminder for anyone considering a big risk on a creative lifestyle change:

“Going indie, starting your own company, being responsible for others, taking financial risks–all that stuff takes a toll. I recently started therapy for the anxiety, burnout and depression that I’ve been experiencing from all of these changes. It’s incredibly common to go through periods of depression while trying to get a game off the ground, especially while you’re in the depths of production and just after launch. It’s also common, if not ubiquitous, to feel at times like an impostor, a fake, or like you “don’t belong” in this industry (and trust me, I have felt that way a lot). As much as possible, try not to isolate yourself. Your friends, family, and community can help stave off the worst of it, and remind you that you’re awesome, that you belong, and that everyone feels that way sometimes.”

Study These References

There are a lot of very useful links above, but if that isn’t enough, here are some more!

Talks

- Darius Kazemi - How I Won The Lottery - This isn’t specifically about games, but if you’re eager to quit your job without a solid plan because you saw an inspirational TED talk, this is for you.

- Tom Francis - How Reviewing Games For Nine Years Helped in Designing Gunpoint - This is mostly about design, and you probably don’t review games, but if you haven’t made a game before, there are a lot of helpful tips here.

- Ryan Letourneau - How to use YouTube streamers to market your game

Reading

- Greg Wohlwend - Don’t Quit Your Day Job - An attempt to talk down “the hobbyist on the ledge” from jumping too soon.

- The Oatmeal - A comic about what it’s like to be creative for a living

- /r/personalfinance - How To Handle Money - A simple breakdown of what to do with your money. Summarized: have a damn emergency fund.

- Gamasutra Salary Survey [PDF] - again, the numbers are old, but still very useful.

Postmortems

- Game Oven - An extremely detailed postmortem of an entire mobile studio, which covers everything from contractor costs and sales numbers to piracy.

- Pass The Buck - Carol Mertz breaks down the financial cost of her card game in great detail, along with links to the resources she used to prototype and print the game.

- Race the Sun - This game originally launched on PC, but not on Steam. They talk about how that hurt their sales and what could’ve been different.

- Sixty Second Shooter Prime - A short look at some of the costs for launching an Xbox One game through ID@Xbox.

Tools

- Vlambeer Toolkit - A collection of links to tools, talks, and more that will help you succeed in making games. Make sure to check out presskit() and distribute().

- Contract() - Adriaan de Jongh’s tool to generate agreements for contract work. Extremely useful for freelancers, but remember: it’s a website, not a lawyer.

- Numbeo - useful for comparing cities when contemplating a big move. User-submitted data, take it with a grain of salt.

Other

- International Game Developer’s Association - There are chapters around the world, find the one nearest you

- Double Fine Adventure - The documentary about one of the most successful videogame Kickstarters ever. It’s a good look at the process and what happens when you run out of money.

- Massive Knowledge - Another Double Fine documentary. This episode is almost entirely about Excel and I love it. The other episodes cover specific jobs, from Project Lead down to Design Intern.

Game Jams

- Ludum Dare

- Global Game Jam

- Itch.io list of game jams

- Indiegamejams.com

- PixelProspector list of game jams

And Finally...

If there’s one message that applies to everyone considering this, it’s simple: do your research. Just as there are a million pitfalls out there, there are also a million jobs you didn’t even know existed. So many people (including me!) say “I always wanted to work in games, but I didn’t know it was actually possible.” Likewise, many people fall into a great job doing what they love and find out it isn’t what they dreamed it would be.

So where does that leave you? Do the research, run the numbers, take the leap. There’s never a perfect time, and as long as you remember to have a backup plan, you’ll figure it out.

Good Luck!

Steve Marinconz isn’t really nearly as pessimistic as he sounds. He just wants you to learn from his mistakes. Watch him make more of them on twitter.