The word anime is often defined as “animation from Japan.” If only it were that simple! When you hear the word “anime”, images of large eyes and colorful hair come to mind. Maybe something like this?

Or this?

Look at that blue hair!

In Japanese, anime is written as “アニメ” (literally, “anime”) and is short for the word animation (アニメーション or animeeshon). The rub is how the word is used, both in Japan and abroad.

In the West, the word anime refers to Japanese cartoons—but it generally refers to a specific type of anime. Namely, Japanese cartoons where the characters have giant eyes (anime eyes) and funky colored hair. The word “anime” is shorthand for this, and sometimes it can be used in a derisive fashion in English. “God, that’s SO anime.” Other times, it’s more neutral and simply being used in a descriptive manner.

But is it always the right word?

Shortening words is common in Japanese. If the language is able to make something shorter, you can bet that it will. So, for example, remote control (リモートコントロール or rimooto kontorooru) becomes rimokon (リモコン), the word television (テレビジョン or terebijon) is now just terebi (テレビ), and the long product name Family Computer (ファミリーコンピュータ or “Famirii Konpyuuta”) becomes Famicom (ファミコン). The language—or at least its speakers—often seem obsessed with making lingo shorter and more compact in daily conversation.

Those examples are foreign loan words, but Japanese words also are contracted and shortened in a similar manner. Loan words are called gairaigo (外来語) in Japanese, but even though they’re borrowed, the words are absorbed into more than the lexicon. They become part of the culture and society. They’re often used to explain ideas and concepts—Japanese ideas and concepts—in a more nuanced way. While they have been born abroad, they’re linguistic immigrants, and eventually, they become Japanese.

Case in point, “anime.” The word itself isn’t that old. Initially, only people in the animation business used the word “animation” in Japan. The general public used different words for the Japanese cartoons that appeared in movie theaters and on television. As website Gogen explains, there was the awkward manga eiga (漫画映画) or “manga movie” or the equally awkward terebi manga (テレビ漫画) or “TV manga”. There was douga (動画), which literally means “moving image” and is widely used to refer to clips and whatnot. Previously, though, all of these words referred to what we’d today call anime. But none of them really stuck. The word manga, of course, now refers to what would be called comic books or even graphic novels in English. In Japan, there’s a long, proud tradition of popular manga finding further success once animated.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the word “anime” first began catching on in Japan. It was also around that time that the otaku fandom as we know it today really started to come into its own. This is not a coincidence. By the 1980s, “anime” was widely used in Japan to refer to, well, anime. But, the word is also retroactively used to refer to works created and broadcasted before the term was in popular use. Take Astro Boy. The character and his look, with those giant eyes, were later used to help define the term anime, long after the show originally aired in the early 1960s.

It’s no accident that Astro Boy’s creator, Osamu Tezuka, the man behind numerous highly influential and pioneering work, is known as “The Godfather of Anime.” His work brilliantly incorporated the American animation he saw and fell in love with as a child, most notably the animation of Walt Disney and Max Fleischer. It was the films of these two men that inspired Tezuka to make his own animation. But what’s often forgotten by modern audiences is just how large cartoon characters’ eyes were in the years prior to World War II.

Fleischer’s most famous creation is Betty Boop. Note that the character’s dog, Bimbo, has even bigger eyes. (Woody Woodpecker is no slouch in the eye department, either.)

“Anime” became a brilliant branding—a way to separate Japanese cartoons from cartoons in the rest of the world. (The other branding, Japanimation, has been used in both Japan and abroad, but as noted in The Anime Encyclopedia, the term evokes a wartime slur.) Warranted or not, “anime” became a way to make the country’s cartoons appear different. When I use the word “anime” in English, you immediately know I’m referring to Japanese animation.

Yet, within Japan, that distinction isn’t always made. For example, it’s not uncommon to see foreign animation also branded as “anime.” NHK refers to foreign animation like Curious George and Boss Baby as “anime,” along with homegrown shows. Sometimes a line is drawn, but not always. In Japan, the Cartoon Network does refer to the American cartoons as “overseas anime.”

Even Disney is not immune to the word. Disney usually refers to its films as “Disney works” (ディズニー作品 or “Dizunii sakuhin”), but many fans call Disney movies “Disney anime” (ディズニーアニメ), with the word “Disney” typically appearing in front.

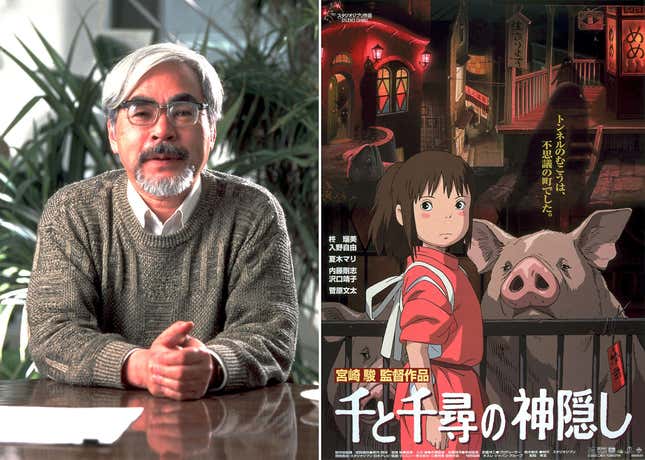

Likewise, Japanese animation companies also refer to their own creations in a similar fashion. Studio Ghibli prefers the term “work” (作品 or sakuhin), steering clear of the term “anime” or “animation,” even if fans do not.

I’d argue that the word “anime” is loaded in English, too, which could explain why Studio Ghibli anime are often referred to as “Ghibli movies” or “Ghibli films” in English. It’s a way for English speakers to separate the works from the baggage of anime. Not everyone does this, though.

These are anime characters, right? Like many anime, there was first a manga version. And then, it was animated. Also, like many anime, this was shown on Animax, a network for anime. So... An exception you say! Maybe.

This is Sazae-san. This is perhaps Japan’s most famous anime TV program. It’s been on television since 1969 and, literally, everyone in the entire country knows it. That cannot be said about other anime.

The characters look rather normal. Nobody has enormous Astro Boy style eyes. That might be because this is based on a comic strip from the 1940s. But in the 1940s, American animation had some seriously huge eyes... And new episodes continue to be produced and aired on a weekly basis.

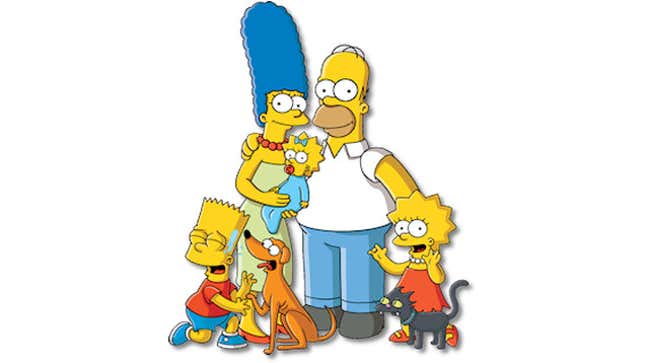

This is America’s longest-running program, The Simpsons. It features characters with funny-colored hair and huge eyes. Is this anime? Well, as of posting, the first line of the Japanese Wiki very clearly refers to this show as an anime—though, an American anime.

The Japanese language can use the term “anime” in an incredibly broad fashion, for everything from Pretty Cure to Popeye. But if you Google image search “anime” (アニメ) in Japanese, you get this:

Most readers look at this and go, “Yep, that’s anime, alright.” Well, Japanese people would look at this and think the same thing. Big eyes are a hallmark.

Like in English, the word in Japanese can refer to a style or a motif. But, as mentioned previously, Japan doesn’t have a monopoly on giant animated eyes. Today, animated characters with big eyes continue to appear in Western cartoons, including modern Disney animation.

However, in Japanese, people will sometimes make refers to anime, saying something “looks like an anime” or “seems like an anime,” but not in a derogatory fashion. Rather, it’s descriptive and used to describe something that can be everything from over-the-top to idealized. (Note: This is also done with manga.) And the understood nuance is that they are referring to a scene or a style found in domestic animation.

While first working on this story, I asked my eldest son, who’s Japanese, what he thought “anime” was. Is Sazae-san anime? “No, it’s too old.” Well, what about Astro Boy? “Yes, because Tezuka made it.” What about Crayon Shin-chan? Is that an anime? “That’s something little kids shouldn’t watch.”

That’s both the beauty and the problem with the word anime. It has different meanings to different people. It’s shorthand. It’s loaded. Is there a way around that? Maybe, yeah. Qualifiers help explain what exactly you’re talking about. “Television anime.” “Disney anime.” “American anime.” Whatever.

Do I think we should use another word than anime to describe a particular style of Japanese animation that many would immediately associate with the connotations that the word anime evokes? No. Not at all. The word is such a part of the English internet lexicon that an attempt to strike it from use would probably just cause confusion. Plus, language just doesn’t work like that.

In English, the word anime will continue to be used to describe animation from Japan—better yet, a certain type of animation. That’s fine. It evokes a style, a look, and even a mood. Still, just remember that sometimes “anime” means more than just “anime.”

This piece originally appeared on May 5, 2015. It has since been updated.

(Updated 3/3/22 with new details)