On the sliding continuum of 'gaming as a worthy pursuit,' board games are respected more than video games.

It probably has something to do with age and endurance — board games have been around for thousands of years, and they've been associated, time and again, with the leisure class. Senet, the first recorded board game in human history, was played by the Egyptian pharaohs in the first Dynasty, and they had their boards buried with them, presumably so they could perfect their strategies in the afterlife. And over a thousand years ago in India, the royal class would play Pachisi on massive, outdoor boards, and use their servants, dressed in brightly colored clothes, as their tokens. Today, we aren't so privileged (or depraved) to use servants as game pieces, but board games certainly have a physical presence — a 'you can touch it' tangibility — that video games lack.

Video game adaptations of board games are often dismissed as mere imitations of the 'real thing.' Shovelware. An easy way to make a buck off of casual players. But despite this reputation, there are some video game adaptations of board games that are well-made, and a select, rare few of them surpass their source material. Take, for example:

Clue

Video Game: Clue

Console: Super Nintendo / Sega Genesis

Date: 1992

The main problem I had with the Clue board game growing up was that I had one sister, and I needed three players for Clue. With two players, you're still wandering into rooms and making suggestions, but since each player learns the same clues at the same time, there's no way to play one player against another, or isolate one player, or do any of the things that makes Clue engrossing. You're just checking boxes and waiting for the mystery to play itself out.

The computer and video game versions solved this dilemma by adding a third, computer-controlled player. Now, finally, I could play Clue unhindered by my non-existent third sibling.

There have been many versions of Clue over the years, but I keep coming back to the 1992 version on the Super Nintendo. In many aspects, it's an entirely different game than the board game. You're not competing against the other players so much as you are playing a massive game of deduction against the House itself.

Let me illustrate this with an example. Let's say you walk into the Study, and through Suggestion, you discover that Mr. Green had the Revolver. If you have the Revolver card, that means that Mr. Green couldn't have done it, because he was carrying the Revolver. Later on, you might discover that Mr. Green was in the Conservatory. Thus, you can rule out the Conservatory as the murder scene.

You see? Unlike the board game, the video game is more preoccupied with 'who was where,' and 'who had what.' On the highest difficulties of the game, you're given obtuse 'negative' clues, like "Mr. Green was NOT in the Kitchen," or "Mrs. White did NOT have the Wrench." You need to stay super-organized to deduce anything out of those. You're only allowed to directly Interrogate your fellow players twice in the entire game. And, same as with the board game, if you make an accusation and you're wrong, the game is over.

Visually, SNES Clue nails it. There are red velvet curtains that rise and fall, beautifully animated cut scenes, and a dark, 'punny' humor: "The Ballroom was filled with the echoes of parties long since dead…" And lastly, Clue has one of the most uncelebrated, underrated soundtracks. The intro music is classy, upper crust stuff, but there's a subtle, dark undercurrent, especially when it switches key halfway through:

And on top of that, each suspect also has his or her own theme. Colonel Mustard has a proud military march theme, complete with snare drums. But my personal favorite has to be Mr. Green's theme:

Damn, that sounds cool. Brass backed by staccato strings — the very definition of gangster.

Scrabble

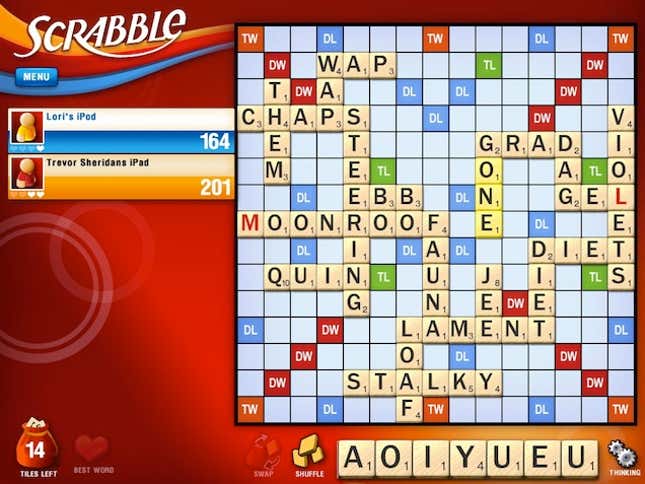

Video Game: Scrabble

Console: Mobile

Date: 2014

Scrabble — the thinking man's board game. As an English teacher, I am expected, by my opponent and any spectator(s), to win every game that I play, which can get irritating. And although I'm a decent, casual player, I was atrocious at Scrabble while I was growing up. I used my blank pieces as soon as I got them, I was never able to play my 'Q' or 'Z,' and I was stuck using three-letter words like "CAT, "DOG," and "EAT." Every so often, I would get an 'S' and immediately burn it by creating "DOGS."

It was the mobile/tablet version of Scrabble that taught me how to play properly. It was instruction through death — I watched in morbid fascination as the computer kicked my ass, over and over, until slowly, I learned. I learned how to create three new words at once. I learned how to strategically shape the crossword, so that my opponent couldn't access the Double Word and Triple Word boxes.

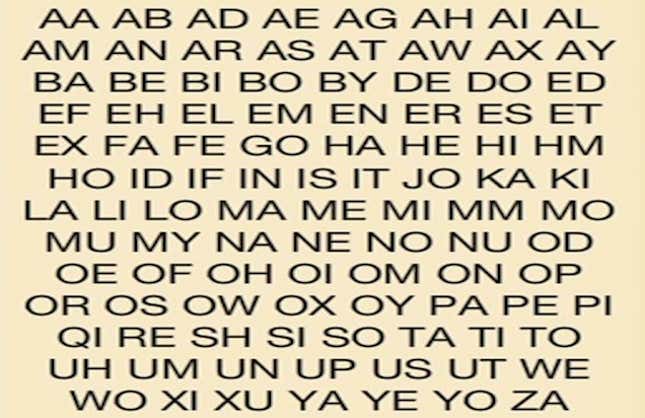

But most importantly, I learned about all of the two-letter words that I never knew existed. The first time I saw the computer playing two-letter words (and racking up hundreds of points), I was shocked; I would never have considered them playable. But once the anger wore off, I got with the program. Here, for your viewing pleasure, are the two-letter words that are legal in Scrabble:

Commit that list to memory, and you'll win twice the number of matches. You're welcome.

Mobile Scrabble gives me as many opponents as I can handle from across the country, and although I love my deluxe edition board at home (complete with a turntable), Mobile Scrabble is the more viable, competitive option. I can play it anywhere I travel against all levels of opponents, and I don't worry about losing 100 tiny tiles.

Sorry!

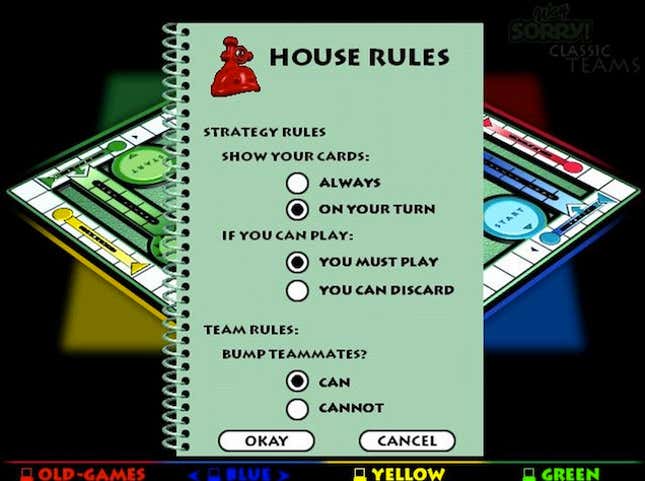

Video Game: Sorry!

Console: PC

Date: 1998

Here's the game that taught us what sarcasm is. There is no better feeling than knocking an opponent off of a slide, sending him/her back to start, and exclaiming, "Sorry!" in your most passive aggressive voice. Instead of having a dice system, like the majority of board games, Sorry! has cards, each of which has a different instruction or ability on it. A dice is an evident, impartial choice maker. But cards? They have a bit more flair — they seem to possess a personality and power that isn't so dispassionate.

I'm not sure if this version of Sorry!, released on CD-Rom in 1998, is objectively superior to the board game. But I certainly enjoy it more, because the developers took the effort to inject some real personality into it.

The CD-Rom contains two different variations of the game — classic Sorry!, of course, and Way Sorry!, which adds extra cards with different powers and abilities. My favorite newcomer is the Happy card, which gives one of my pieces immunity for a single turn. Beyond this, there are customizable options, including many of the popular house rules that I followed in elementary school with my friends. The key word here is 'optional' — you can always play the official version if you want to.

But what really makes this adaptation special is its humor. Each of the playable pieces has its own personality and quirks. The pieces trash talk each other, bicker amongst themselves, and even support each other in times of need. It's the right amounts of kitschy without being corny.

And the animations complement the snappy dialogue perfectly. One piece takes out a sword, and slices another piece to bits. Another piece gets on a horse and rides to the next square. Another piece turns itself into a spoked wheel, with a little boot on each spoke. The variety definitely keeps your attention.

The game's budget probably wasn't high, and the visual look of the game doesn't stand the test of time. But it's both inspiring and heartwarming — to see that such detail was placed into such a modest project. The developers clearly cared about and loved their work, and it shows.

Chess

Video Game: Chessmaster XI

Console: PC

Date: 2007

I love chess, even though I'm terrible at it. From what I can tell, my main problem is that I'm too passive. That's an understatement; I'm more concerned with not making a stupid move than making the right move. This is how most novices play — it's not really about who has the best strategy. It's about who can make the most moves without making a colossal blunder. A beginner match resembles a Rube Goldberg experiment — every piece is in line to trigger another piece, and whoever makes the first mistake is going to lose everything.

I always knew that this wasn't the proper way to play — there had to be an aggressive, offense-based style that wouldn't get my Queen killed. But I didn't have the courage or the foresight to figure it out until Chessmaster showed me how.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSu1h2oFCKoChessmaster wasn't my first option. I originally tried to teach myself the opening game by buying a chess book. I bought Capablanca's A Primer of Chess, and I couldn't make heads or tails of it. His explanations were clear enough, but there's nothing like having the board right in front of me, with a voice to explain the moves clearly, step by step, until I understood them.

Chessmaster allows for all of that, plus more. It has a backlog of 900 famous games — each of them broken down in a visually friendly style. My favorite feature is the sophisticated AI. I can play against a computer that's programmed to behave like Bobby Fischer — a vicarious thrill for anyone with knowledge of the game. And after a single-player game, Chessmaster can examine my moves, and analyze their respective strengths and weaknesses. Outside of actually hiring a tutor, it's difficult to think of a better learning experience.

I don't suppose that Chessmaster would be as engaging for a master player, but I've never been and never will be a master player. For me, Chessmaster provides a level of interactivity that the board never gave me. I'm still making wrong moves, but I'm slowly starting to see the moves I should have made. I've never played more competitively, or tried so hard. Thus, I've come to love the game more than ever, and I have Chessmaster to thank for that — for cultivating my love, and for making it deeper, more intellectual, and more resonant.

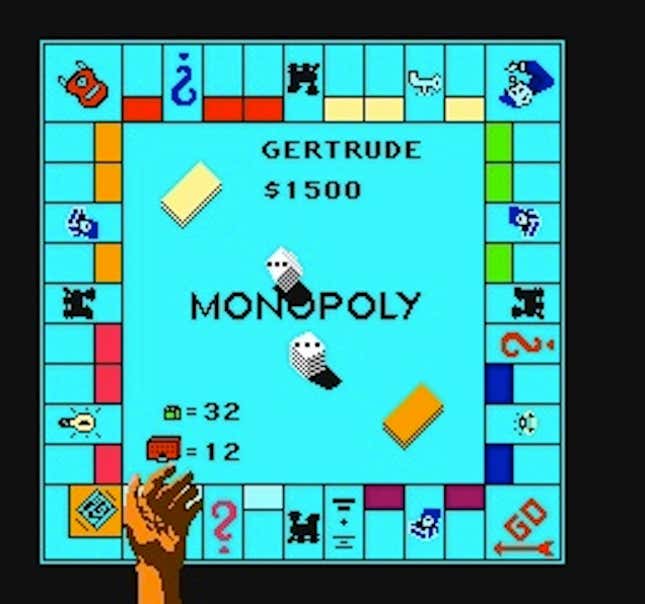

Monopoly

Video Game: Monopoly

Console: Nintendo Entertainment System

Date: 1991

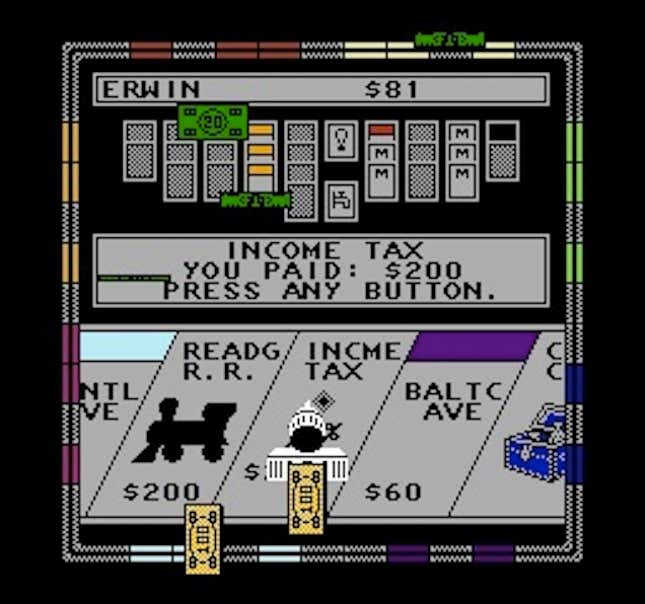

There have been over 20 years worth of Monopoly adaptations since this gem dropped on the NES in 1991. But it's still, without contest, the best rendition of the original — both enhancing what makes the board game great, and patching up its handful of flaws.

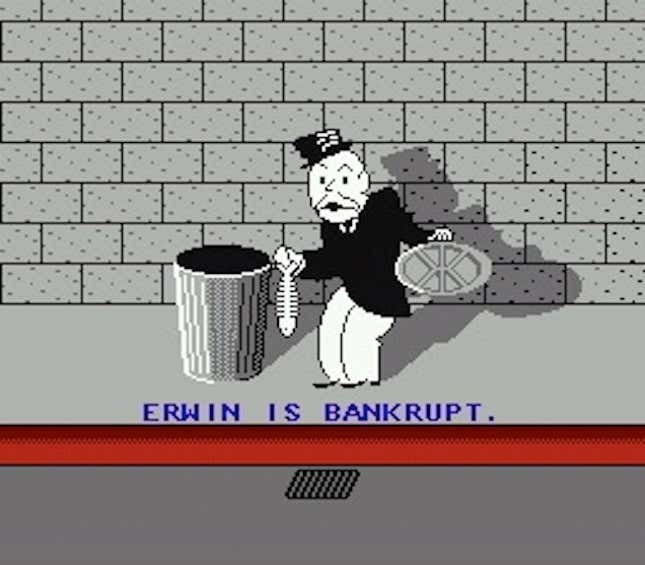

My memories of playing the Monopoly board game as a child are unpleasant. A Monopoly loss kills the soul. First, you lose your cash. Then, you mortgage all your properties, which puts you even deeper in the hole. You convince yourself that you'll unmortage them at some point, but in your heart of hearts, you know that you won't. The only cash flow is the 200 dollars you get from passing GO. But then, you land on Income Tax, and now, you're truly fucked. You hope, against hope, that you'll make it around the board without landing on an opponents' property. There is no quick, firing squad execution in Monopoly — you're hanged, drawn, and quartered over the course of multiple turns.

Monopoly has a way of bringing out the worst in people, mostly due to its one-sidedness. It's the Stanford prison experiment on a small scale — those who are winning get petty and mean, and those who are losing get angry. Several games of Monopoly went unfinished in my household, because everyone was too pissed off to continue.

On top of that, the game is long — monstrously long. You could have a birthday in the time it takes to complete a Monopoly game. It's the endless exchange of cash — the adding, the subtracting, the making of change — that makes a humiliating process even more protracted.

Obviously, all video game versions of Monopoly can instantly calculate the rents and mortgages, and that eliminates one of the main time wasters. But what distinguishes the NES version from the others is that the entire game is incredibly fast and efficient.

The tokens move across the board at a rapid pace. It's one press of the A button to buy a property, and it's immediately the next person's turn. The menu is intuitive, and all of your options — buying houses, mortgaging properties, and even checking assets — are only a few actions away. Later versions had prettier animations and a more polished presentation, but nothing beats the NES version's 'no frills' approach. There's elegance in simplicity.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSu1h2oFCKo

That's not to say that NES version doesn't have cutesy animations — the cash register that eats your rent, the animated Community Chest Cards, and so forth — but all of these cut scenes and animations are skippable. There's even an option in the menu to make the computer opponent skip them. And suddenly, the entire game seems less sadistic. The rents are less oppressive, the jail terms seem shorter, and even the bankruptcies hurt less when everything moves at a fast, efficient clip.

Today, whenever I play Monopoly with friends or family, we always haul out and dust off the NES. We fight less, we laugh more, and we focus on an oft forgotten aspect of the game — strategically trading and forming alliances. And we always finish our game in one sitting.

Let's be clear.

You should not play these video games to the exclusion of their board game counterparts; in fact, you need a prior knowledge of the board games to appreciate what the video games offer. But still, when I want to play Clue, Scrabble, Sorry!, Chess, or especially Monopoly, I find myself turning on a screen rather than opening a box. And although this may be sacrilege to some, it feels like progress to me.

Top art by Tara Jacoby

Kevin is an AP English teacher and freelance writer from Queens, NY. His focus is on video games, American pop culture, and Asian American issues. He wrote a weekly column for Complex called "Throwback Thursdays," which spotlighted video games and trends from previous console generations. Kevin has also been published in VIBE, Salon, PopMatters, and Racialicious, and he will soon be published in Joystiq. You can email him at kevinjameswong@gmail.com, and follow him on Twitter at https://twitter.com/kevinjameswong.