Here’s a theory: Final Fantasy is defined by how it sounds.

No, I don’t mean the music—although Nobuo Uematsu’s stirring soundtrack is as pivotal to Final Fantasy’s success as anything else—I’m talking about how it sounds. The chime of a menu cursor. The squeal of an NPC’s dialogue box. The thunderous jolt of a random encounter. That stylish sound design has become a defining aspect of the series, and it’s been there from the very start.

Just watch a few minutes of the first Final Fantasy and you’ll notice it right away. In fact, if you’ve got some time, here’s 20 minutes of me playing:

In just a few months, Square Enix will release Final Fantasy XV, a game that’s been in development for over ten years (give or take a few reboots). More so than with any past numbered Final Fantasy, the future of the series rests in this, Square’s stab at defeating the HD giant that has hounded them for so long. If this game fails, it will have a cataclysmic impact on both the series and the company behind it.

Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that FFXV is going back to its roots. The first Final Fantasy, released in 1987, was a last-ditch effort to save the company through a big RPG with high-end graphics, a fantastical world, and a massive marketing blitz. Now we’ve come full circle.

To prepare for FFXV, I’m starting a new project here at Kotaku. For the next five months, I’ll be digging into every mainline Final Fantasy game, in order, and taking a look at how the series has evolved over the past 30 years. Why has Final Fantasy resonated with so many people? What makes it so special? What exactly does it mean for a game to feel like a Final Fantasy?

Answering those questions calls for a trip back to the late 80s, when a company called Squaresoft was floundering, unable to find much commercial success with its slate of interactive adventure games and space shooters. As the myth goes, Squaresoft was facing bankruptcy when their top designer, Hironobu Sakaguchi, decided to make a role-playing game that would be heavily inspired by Dragon Quest and Lord of the Rings. He thought it’d be the company’s last game ever, so he called it Final Fantasy.

With the opening arpeggio of Final Fantasy’s prelude, which started playing as soon as you blew on the cartridge enough times, it became clear that this was a special game. Few of the ideas were unusual—Sakaguchi had clearly played a lot of Wizardry—but everything felt polished in a way that other games of the time had never quite managed. The music, the art, the sprites, the graphics, the combat backgrounds, the NPCs, the massive world, and yes, the sounds: they all blended together to create something that felt truly great. If Dragon Quest was a hamburger, Final Fantasy was filet mignon.

The story: Chaos has dominated the land. The waters are stirring. The earth is rotting. The princess has been kidnapped. Something is dreadfully WRONG with the world of Final Fantasy, and it’s up to you to fix it. Your four adventurers, each of whom wears a different costume that signifies a character class like Fighter, Black Mage, and Thief (a shtick that would be used in many Final Fantasys to come), must go out and save everything.

The gimmick: Fetch quests! One early quest-line in the game asks you to go find a CROWN to bring to an evil king who stole a CRYSTAL from a witch who has an HERB that will wake up an elvish prince who gives you a KEY that lets you unlock a chest full of TNT that will let you open up a canal and sail to the next region. Today’s RPGs tend to be better at masking fetch quests, usually by sprinkling them with cutscenes or making them feel unusual. The first Final Fantasy, on the other hand, is unabashed in its love of the mundane.

What makes it ‘feel’ like Final Fantasy: Everything, really. You can see the building blocks all throughout the game: the musical motifs, the character classes, the airship, the four elemental ORBs that each of your homeboys has to restore. Later Final Fantasys, unshackled from character restrictions, would call these Crystals. If to “feel” like a Final Fantasy game is to feel like you’re exploring a surreal new world full of surprises and incredible music, this one plays the part. (We’ll get into what “feeling” like Final Fantasy really means as this series goes on.)

What’s unusual: One odd thing about the original Final Fantasy is that it doesn’t actually feel much like a JRPG. Most Japanese role-playing games are user-friendly, offering save points before every boss battle and distributing a constant stream of helpful items and equipment. Who among us hasn’t found themselves on the final boss of an RPG with a surplus of Megalixirs because we never needed to use them? The challenge in most JRPGs, if there is any, is customizing and leveling your characters so they’re prepared for every battle. Final Fantasy is different. It’s more of a dungeon-crawler, forcing the player to make difficult decisions at every step. Do you use your cure magic on level two of the Ice Cave or wait until you’re closer to the boss? Do you risk walking through those lava tiles so you can see what’s in that chest? Should you go back to town and heal up or risk getting killed by a boss and losing hours of progress? Final Fantasy, unlike most of its successors, is often brutal and unforgiving.

Cid: Nowhere to be found! Stay tuned.

The best character: Fighter, a kickass ginger who beats out the other classes because he’s useful from the beginning. Other classes, like the Black Mage and Thief, require some investment before they turn into killing machines.

The best piece of music: Prelude, mostly by default. I’m partial to many other tracks, like Matoya’s Cave and the Ship music, but Prelude is the song that represents Final Fantasy best, not just as a game but as a series. There’s nothing else as iconic.

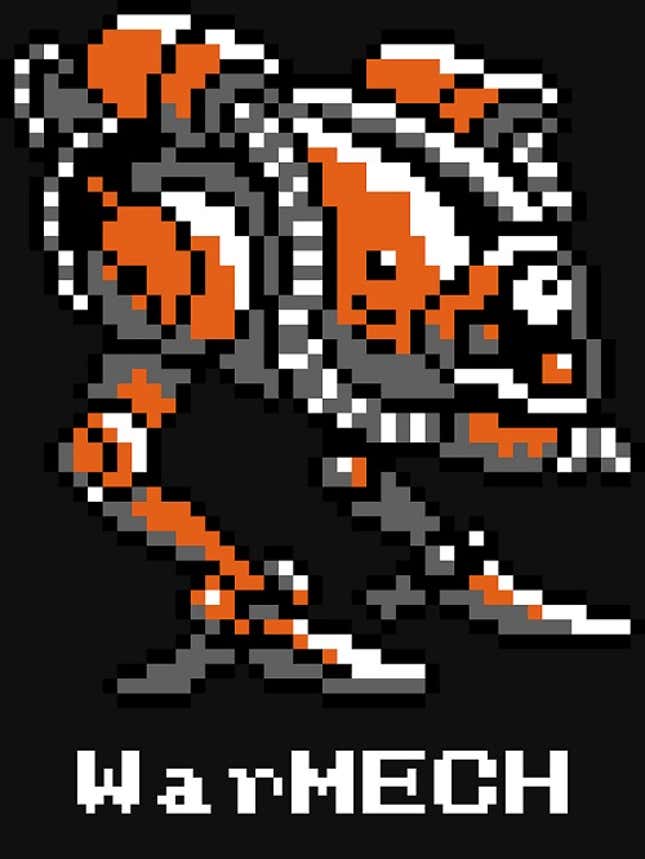

The worst boss: Warmech, a terrible robot who served as sort of a prototype to the Ultima Weapons and Ozmas of future games. The big difference between Warmech and those other optional bosses? Warmech ambushed you. If you get unlucky while walking on a certain bridge in a certain tower, bam, it’s game over for you. Like I said: unforgiving.

Does it still hold up? Not really, in part thanks to a major design flaw: if you kill one enemy creature and there are others remaining, any characters that were supposed to attack or cast magic on that creature will still attempt to do so, leading to an irritating “Ineffective” message as your party wastes their turn. Rather than automatically target the next creature in line, your lovable dumbasses will just swing their swords in the air. Later versions of the game fixed this problem, so if you want to see how Final Fantasy started without dealing with annoying combat, go with the GBA version.

One last thing you should know: Pressing A+B together a bunch of times while sailing around the ocean will take you to the first Final Fantasy minigame ever, a tile-sliding puzzle that somehow provided many hours of fun to two-year-old Jason. His standards were way lower back then.