Before we even start talking, General Mittenz asks me if we can stand for the duration of the interview. “For me, right now, I’m having a massive anxiety attack,” he explains while fidgeting nervously. Standing and moving around helps. A little.

On Twitch his name is General Mittenz. It’s not his real name of course. That’s James, though he’d prefer not to make his real last name public. Let’s just call him Mittenz.

Before meeting Mittenz at TwitchCon in San Francisco, I wasn’t sure what to expect. He’s not a big Twitch star, so his reputation couldn’t precede him. I knew he had a slightly uncommon shtick—a talking World War II general kitty cat where his face would normally be in streams—but I didn’t know what to make of it. Cats are, after all, Internet cruise control for popularity. I’m not proud to admit it, but even I—in my lonelier moments—will toss a cat pic up on Twitter in hopes of receiving a star storm of precious, precious approval. So, waiting in the TwitchCon press area, I was a bit worried. Was I about to meet the flesh-and-blood embodiment of a gimmick? Was our talk gonna be one-note?

Mittenz and his wife, Mollie, approached. Mittenz is tall, lanky, dark-haired, and—crucially—doesn’t wearing a giant cat mask. He began talking, not about cats and cheap comedy, but about how streaming saved his life from anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder. The goal of his channel? To pass that on—to help other people struggling with everything from stress to the death of loved ones get through their day.

Mittenz is a boisterous, upbeat person. His gestures are big, his voice(s) strong and resonant. He mentions his “crappy childhood” with a chuckle so disarming you’d swear he practiced it.

A few sentences later, he’s telling me that he believes being entertaining is a coping mechanism.

Mittenz grew up in rural Maine, raised by a mother and father who had a tougher than usual time. His father, he told me, was a Vietnam war vet who’d been honorably discharged and labeled mentally disabled. He said his father was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and PTSD, says he led a sheltered childhood, “sequestered away from the rest of the world.”

Mittenz told me that when he was 16, his mother just up and left. No warning. By this point, he said, all of his brothers had already moved out. It was just Mittenz and his father. For months.

“I was never scared of God or hell,” Mittenz says, “but I was scared of my father.”

Mittenz doesn’t blame his parents. He thinks they were afraid. He can relate.

Years later, he told me, he became his father’s best—and perhaps only—friend. “During my senior year at college, my mother (finally) divorced my father,” Mittenz explained. “She moved back to Maine, and [my father] stayed in Arkansas. At this point, neither my brothers or I spoke to him. Realizing that my father was a flawed, human individual, I reached out to him via hand-written letters, asking for advice about random stuff. Over the course of three years, we developed a relationship as men. Not as father and son, but as equals. Snail mail evolved into email, and email into phone calls and texts. When my girlfriend (now wife) and I broke up for six months, I was 23 and I stayed with my father. After being each others ‘go-to’ friend when in need, we operated like an old couple. We both had the same thought patterns, we finished each other’s sentences, and I’d never felt closer or more lucky.”

His father never really healed, though. Mittenz said that he had to talk him down from suicide repeatedly. Finally, he told his father that he couldn’t take it anymore; the emotional strain was like an anchor wrapped around his ankle, pulling him down, down, down. A few months later, his father killed himself.

What followed was the toughest year of Mittenz’ life.

Mittenz discovered Twitch in 2014. He was struggling. His problems were closing in on him, stalking and leering. He didn’t feel like he could talk to anybody about what had happened—not even his wife. He was on the verge of, as he puts it, “going out like my father.”

At the time, he was using video games to escape—specifically, Dark Souls. In more ways than one, he needed help. He went to YouTube. There, he discovered the speedrunning community, and he noticed they all had handles for this thing called Twitch. He fell into a small but tightly knit group of streamers, and finally—little by little—he began to let out the demons he’d been keeping bottled up.

“It was the kind of thing where I couldn’t open up to anyone about my dad’s death, but I was able to open up to those people,” Mittenz told me, visibly loosening up a little. “And it wasn’t like I was just a username whispering to other usernames. At that point, we had each other’s phone numbers. It’s a tight community. Texting back and forth. That really saved me at one of the darkest points in my life, hands-down.”

“No one saved me as a child, and I couldn’t save my Dad, but the family I found on Twitch did save me.”

Mittenz sought counseling. He found out what he was up against—anxiety, bipolar, PTSD—and he learned how to combat it, both with medication (which he said he uses sparingly) and tricks that keep him in the here and now.

Twitch was his catalyst for self-improvement, a life-saver. So, after years of working dead-end jobs stocking shelves (and eventually trying to write a book), Mittenz decided he wanted to be a professional streamer.

Mittenz told me that he throws up before every stream. He has anxiety attacks, and well, one thing leads to another. Given his particular background and set of issues, streaming has proven to be a fraught journey. And keeping his anxiety from bringing up all-too-fresh memories of breakfast was only half the problem.

“I streamed under another account [before creating General Mittenz] for 14 months,” he told me. “Typical guy in a corner with a green screen, etc. I streamed every day, six-to-ten hours. Every stream, I threw up three times before I went on. But it wasn’t going where we wanted it to, and frankly, Twitch is an evolving beast. I started at a time when I was looking up to people who’d gotten big, like, two years before—three-and-a-half years, at this point. It’s completely changed. After almost a year-and-a-half of streaming, I realized this was a different game.”

He rammed his head into Twitch’s ceiling over and over, but he just couldn’t break through. The key to success, he found, was no longer just being a solidly entertaining person who played video games. Twitch had become populated, saturated. Millions of people were streaming. Mittenz needed something else. To make matters worse, he continued a common theme in his life: he went at it alone.

“It was all me,” he said as his wife, Mollie—now also his manager, agent, and programmer—nodded in agreement. “It was my thing. My wife would do her job, and then she’d come home and help because she’s brilliant with the tech side of things. But I’d be like, ‘Nah, this is my thing.’ Until I needed something photoshopped.”

He chased success relentlessly. He just needed to become a Twitch Partner, he told himself, and then he’d have this thing locked up. But it was eating him up inside, sending him back to the dark place that streaming originally helped him escape. “I was looking at numbers, looking at statistics and all of that,” he said with a regretful sigh. “It finally got to the point where my passion was gone. I just wasn’t into it. The stress, anxiety, and depression were back. All of it just kinda hit at the same time.”

So he made a tough decision. After all that work making friends, building his public persona, and establishing himself, he abandoned his channel.

Perspective. That’s what Mittenz needed, and that’s what spending months away from his old online identity gave him. He went dark on Twitch, Twitter—everything. Just kinda disappeared.

And he planned.

Collaborating with Mollie, Mittenz spent months trying to come up with something that’d help him stand out when he created a new channel. They wanted to launch without any connection to Mittenz’ previous channel, so they could test if this thing could be successful on its own merits. Whatever they came up with, it would have to hide Mittenz’—or rather, James’—identity. It would have to be an alter ego.

During this time, both Mittenz and his wife became increasingly anxious and lonely. They’d cut themselves off from their outlet, from people who felt like family, and their real families were on opposite sides of the country. Finally, it reached a breaking point, and that’s when the concept of General Mittenz was born.

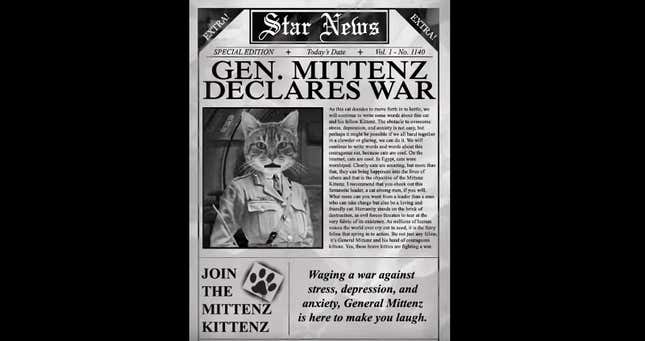

“I was pacing back and forth—just pacing and pacing,” Mittenz said, also pacing right in front of me. “I was like, ‘We need something! Like... like... like a cat in a uniform and his name is General Mittenz or something.’ And my wife goes, ‘Wait. That’s good.’ I was like, ‘Naaaaaah.’ But she was like, ‘No, really. That’s good.’”

So Mollie set to work creating the art and a program to animate the General Mittenz character’s mouth and facial features. But still, they needed more. At that point, all they had was a gimmick, and that was a trap they refused to fall into.

“A gimmick will only get you so far,” Mollie told me, explaining that you can grab someone’s attention with a gimmick, but you can’t hold it for long. You need substance to back it up.

They pointed to inspirations like Futuremangaming—who dresses up and plays a character From The Future seeking to defeat evil video games that will ultimately lead to mankind’s downfall—and DomesticDan, who streams himself both playing games and teaching people how to cook. The idea, they explained, is to create a unifying theme—not just a gimmick. That, they think, is where Twitch is headed: characters and concepts, creative people doing a bit more than just playing games.

So Mittenz and Mollie had their hook, but they didn’t have their concept. And without that, General Mittenz was DOA.

“We wouldn’t have gone live if we didn’t have a full concept,” said Mollie. “So he’s a general, but we kept coming back to the question of what he’s fighting.”

At this point, they’d been cooped up for months, and the stress and anxiety was getting to them. That’s when the idea hit them:

“We were spitballing,” said Mittenz. “Is he fighting against evil games? And I’m walking around, having an anxiety attack the whole time. ‘What’s he fighting against what’s he fighting against what’s he fighting against’ while doing all my tricks to calm myself down. ‘What he’s fighting against... is stress.’ It was so obvious at the end of the day. I have a lot of experience with it. I’ve picked up so many little tricks that I can pass along to other people.”

But still, there was one last dilemma: how would they handle the alter ego thing? How would they build up a forthright, relatable character while keeping James’ identity a secret?

“We talked about being like The Gorillaz,” said Mollie. “You know the characters, but not necessarily the people.”

“We thought a cat mask could be a major thing [at events],” added Mittenz. “Like, ‘Who is he? Who’s this guy in a cat mask?’ There’d be a mystique about it.”

But they realized something felt off about that idea—almost disingenuous. People like watching streams because it feels like they’re hanging out with friends. For Mittenz and Mollie, their old Twitch friends were like family. Keeping secrets? It felt completely at odds with everything they’d learned.

On top of that, Mittenz couldn’t get behind the idea of telling people to face their fears—to fight stress, anxiety, and depression—while hiding behind a mask.

“It all felt wrong,” says Mittenz. “Plus, having all this anxiety, imagine me walking around in a cat mask all day.”

In the end, they decided to keep Mittenz’ real identity on the down-low for a few weeks, and then—at events like PAX and TwitchCon—tell EVERYONE. It worked like a charm. Old friends from their streaming community were thrilled to see that they were back, and they helped spread word of the channel and its concept. Personalities like ShannonZKiller, Ezekiel_III, and MANvsGAME—who Mittenz and Mollie had met during Mittenz’ previous attempt at streaming success—latched onto the idea and told people to check out General Mittenz’ channel.

While Mittenz and Mollie still haven’t reached Twitch Partner status (they’ve only been at it for a few months), they’re doing far better now than they were at this point in their previous attempt, and they owe a lot of it to the people they met during their first go-’round.

“We’d be nothing without everybody else,” said Mollie.

“If we’d hidden behind the mask, we wouldn’t have that,” added Mittenz. “Being able to face that fear and say, ‘You know what? It doesn’t matter if people judge us for shutting down the old channel.’”

On stream, Mittenz is jovial and inviting. He greets people individually. He asks them how they’re doing, what’s going on in their lives. Sometimes he uses his regular voice, other times he sounds silly or extra loud. He wants to create a space where people can relax and be honest, where they can voice their troubles and also laugh at his, frankly, ridiculous character.

“People come in and talk,” said Mittenz. “Sometimes it’s crazy things like ‘My brother killed himself.’ We’ve heard that. But there are also more ordinary things. People saying stuff like, ‘I hate going into my job every day, but I tune in every lunch break.’ Joel5150 tunes in every lunch break that he has. So it’s always, ‘Hey Joel, what’s for lunch today?’ And it’s always chicken and rice.”

Mittenz tries to offer friendly comfort and advice, and he wants to create a community that will do the same. He wants people to come away from his streams feeling positive—trying to actively be positive—even when things are bad.

“Since I’ve been fighting this stuff for 20 years, I’ve picked up so many little tricks,” he said. “Like, if you’re in a meeting and you have a panic attack. I’m talking heart rate over 190. I’ve been there. There are things you can do, things people can’t see, to take your mind off it. I’ve learned a lot from seeing counselors for so long, doing tons of research. I don’t want to have panic attacks all the time. I’m constantly living in fear. I have PTSD. I’m bipolar. Every day is a battle. But that’s true for everyone, to an extent—whether you’re dealing with really heavy stuff or just stress, the grind of working to live, not living to work.”

There’s also a hidden side benefit to Mittenz’ approach: it keeps Mittenz and Mollie accountable—to the community and themselves.

“In my personal life I’d say I’ve come to realizations [about positivity] multiple times,” he explained. “But then you fall away from it. This channel keeps me accountable to it. I’m the one saying this stuff. It’s on the letterhead or whatever: ‘We’re fighting against anxiety!’ So every day that’s the first thing on my mind. The channel and my community help me as much as I help anyone else. I’m not sure they know how much they help.”

Practice what you preach.

It’s one thing to say all this stuff about positivity and pulling yourself out of dark spirals; it’s another thing to actually make it work. I admit, even after talking to Mittenz for such a long time, I was skeptical. I mean, if the solution to unhappiness was as simple as, “Just stop being sad,” I don’t think anyone would ever take the painful journey down to frown town. But I think there’s a little more to it than that.

While writing this post, I fell into a bit of a funk. I had a bunch of false starts. I didn’t know quite how to handle the subject matter, and—as is The Writer’s Way—I decided that made me the worst writer on Earth and rendered any and all previous accomplishments null and void. Meanwhile, my relationship hit an unexpected rocky point, and that dominated a lot of my time—not to mention my mental and emotional bandwidth. My work productivity went down the toilet, and also the toilet laughed at me and gave me a swirly. I stopped responding to messages from friends and co-workers because I was just too tired (sorry, friends and co-workers).

It’s been a shitty few days, is what I’m saying.

I had this moment, though, after watching one of Mittenz’ streams. I was laying out my schedule for the next day, and I looked at it and thought, “I’m gonna sort my relationship issues tonight, and I’m actually going to get all of my stuff done tomorrow. No excuses.”

And I did. I’m feeling much better now, having realized how tempting it is to decide everything you care about is fucked after a few bad days, how quickly you can lose perspective. It’s easy to dig that hole, but sometimes it’s also easier than you’d think to dig yourself out. Solving problems—whether that means full-on depression or merely an especially insistent case of The Sads—is never that simple, but it’s a good start, a strong foundation from which to build.

Mittenz’ streaming style may or may not be your cup of tea, but the mentality behind it is infectious. (The, uh, good kind of infection, to be clear.)

Mittenz’ second lease on life as a streamer is just getting started. His new channel has only been going for a few months, and he recently broke a thousand followers. He tends to pull only a handful of viewers at any given moment. He hasn’t seen the need for any Twitch chat moderators (yet).

He doesn’t know if he’ll actually succeed this time around—at least, in the monetary sense of the word. But Mittenz and Mollie have already made their peace with, well, whatever happens.

“We had to evaluate why we’re doing this,” said Mollie. “Because what if we never get partnered?”

They have a timeline. They have a plan. And they have a plan in case that plan doesn’t work out—a point at which they’ll say, “Oh well, we gave it our all.” For now, though, Mittenz is trying to live in the moment instead of fretting about what lies ahead.

“I wake up every day having a bad day,” he confessed. “My back’s shot. My knees are gone. I’ve had a really crappy life! I wake up every day struggling, and I know there are other people out there like that. Streaming is extremely stressful, but I can go into my channel, start streaming, and ten minutes later I’m already feeling a little better. Because people are coming in going, ‘This is the highlight of my day. I’m so glad you’re here.’”

Top illustration by Jim Cooke.

To contact the author of this post, write to nathan.grayson@kotaku.com or find him on Twitter @vahn16.