“What they teach you in juvenile halls or in youth offender facilities is not about education,” researcher Dana Ruggiero told me during a recent phone interview. “It’s not about making better choices. It’s literally just a rhetoric, and then they put you back into the same system you came out of.” She started Project Tech, a program focused on teaching game design to young people in prison, to help break that cycle.

Project Tech is a program intended to help juvenile offenders find a future through game design. Through using basic tools like Twine and Scratch to design short games about real-world issues, Project Tech gives program participants the basics of writing, programming, visual art, and collaborating with others. The program doesn’t intend to teach youth how to make the next Call of Duty or Minecraft, but it does give them a new, more engaging way to learn useful skills and engage with the societal systems that led to their incarceration.

While Project Tech began at Purdue University in Indiana, Ruggiero and her main collaborator, a youth worker named Laura Green, currently administer it at secure children centers in the UK, where they both currently live. Secure children centers are for youth between the ages of 10 and 16 who’ve been found guilty of crimes. These centers prioritize education, as opposed to youth offending facilities, which treat education as a privilege, not a right, and keep kids locked in their rooms for most of the day. Ruggiero and Green work mostly in secure children centers, but they’re also in the early stages of working with a youth offending facility in Wales.

Project Tech begins with brainstorming and prototyping on actual, physical surfaces, as opposed to computers. Game developers sometimes use pencil and paper or post-it notes for this—to be able to move objects around and simulate how a game might work—but Ruggiero explained that she’s not allowed to do that. “We can’t give them pens or pencils or scissors or anything like that, because they might make weapons,” she said. “We have to do it with what they allow us to use, which is soft markers and whiteboards that are nailed to the walls.” So instead they brainstorm and do simple logic trees to illustrate the way choices function in games. They also do team-building exercises before cutting their teeth on a starter narrative game based on a news story about a man who was murdered by teenagers.

It’s heavy stuff, but that’s just the beginning. After this introduction, participants spend the following weeks envisioning and learning how to make games in simple game-making engines like an interactive narrative tool called Twine and (occasionally) a simple programming language called Scratch. Participants make a game in these programs based on a prompt Ruggiero and Green provide.

“[The prompt is], ‘Can you create a game about a social issue that led to you being in prison, and can you make this for somebody younger than you?’” said Ruggiero. “We tend to motivate them by saying, ‘Think of your younger cousins. Think of your younger brothers and sisters. What would you want to teach them about the reason that you’re here that would help them not make the same mistakes you would make?’”

Ruggiero added that she’s worked with incarcerated youth who were in prison for everything from car-jacking to drug-running to armed robbery. Choice, however, is at the heart of almost all of the games they make, because Twine, one of their main tools, is best for making choice-driven narrative games.

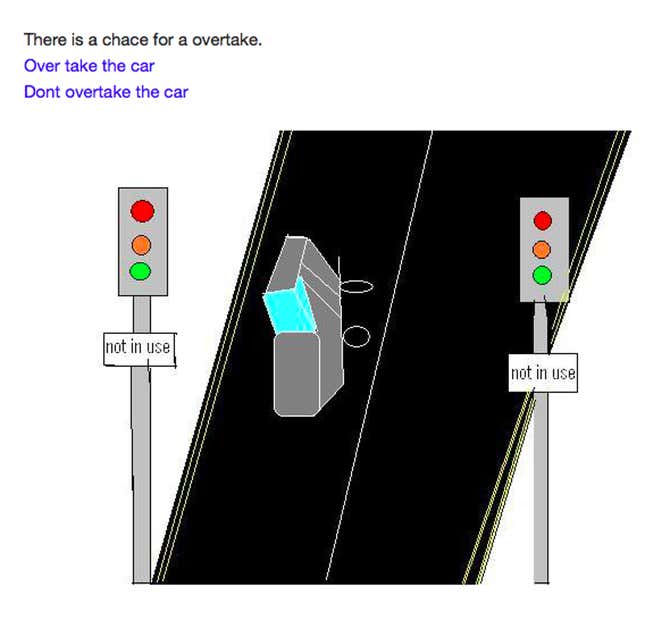

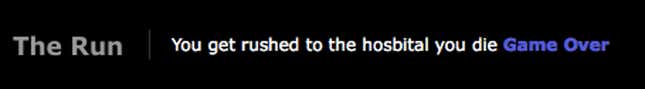

Ruggiero gave me examples like The Run, a game about people who’d just gotten out of prison falling back into crime and, depending on the choices you make, dying or going to jail. There’s also one called Make A Choice Driver where you face the consequences of driving irresponsibly after stealing a car. Consequences in the game include everything from 20 years in prison for hitting somebody to a crippling injury after somebody else sideswipes you. The game suggests your best bet is to not take the car in the first place.

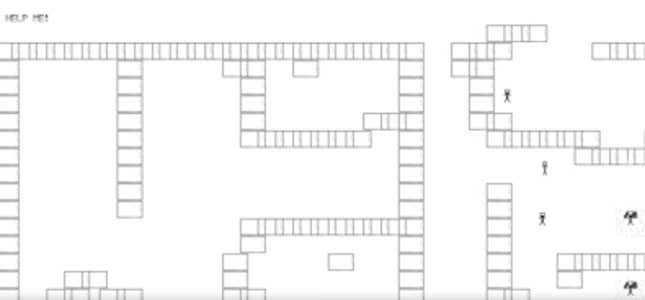

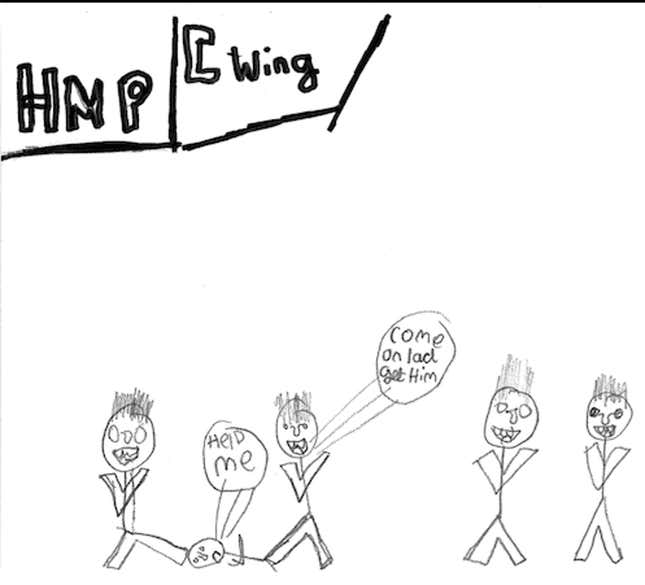

Ruggiero told me about a game called The Escape that was about a boy trying to rescue his sister, who is a victim of parental abuse. It was made in Scratch rather than Twine, so it was more elaborate than other projects.

“It was a top-down game, like Zelda,” said Ruggiero. “You run through the house, and you have to avoid the witch, which is this woman. You have to rescue the little girl, and the little girl keeps saying, ‘Help me, help me, help me,’ and she keeps moving. Once you’ve rescued her, you go to different parts of the house looking for the little girl’s things. Then you escape from the house with her.”

She added that kids have also made games about littering, running from the cops, and cyber-bullying. In all cases, Ruggiero’s goal is for kids to engage not just with their topics, but with the societal systems surrounding them. She admitted, however, that it’s sometimes hard to tell if she’s getting through to them.

The centers where Project Tech is active use what Ruggiero described as a “very carrot-on-a-stick” approach. If the youth in them behave, they get to listen to music or have posters in their rooms. If they don’t, these privileges are taken away. The message, Ruggiero told me, seems to be that if you follow the rules, people will like you and life will work out. School good, drugs bad, etc. The education they receive is very repetitive and reductionist, and Ruggiero doesn’t think it does kids any favors. She worries that some of the games kids end up making are, for them, just an extension of rhetoric.

“When we talk to them and when they design games, we don’t know what we’re getting,” she said. “We don’t know if we’re getting what they actually believe or what they think they have to say in order to be successful [in the secure child center]. It’s a very strong rhetoric that comes through [in these facilities], and it’s very behaviorist, and it’s based off the way that they teach them there. It comes through big time in the games.”

While secure child centers are full of young people, they are still, functionally speaking, prisons. As a result, Project Tech does not always run smoothly. “There’s tons of infighting,” said Ruggiero. “Last time we ran it, we had eight kids to start with. That went down to five very quickly because of fighting [between kids], because of cursing out the staff, things like that.” She mentioned that kids can get frustrated during the program and lash out, going so far as to throw chairs at people. One time, Ruggiero and Green had to call off an end-of-program showcase because somebody attacked a teacher, and there was blood everywhere in the room they were going to use. “These are kids,” Ruggiero said before a pregnant pause. “But they’re dangerous kids.”

For those reasons and many others, Project Tech faces an uphill battle. Ruggiero and Green want to expand it, but right now they’re short-staffed and working full-time jobs in addition to running the program when the opportunity arises. They’re applying for grants so they can get funding and involve more people, but operating on this small of a scale, it’s nearly impossible to show concrete evidence that Project Tech is having an impact. It doesn’t help that UK institutions put serious time and logistical constraints on the program. Two weeks is an exceedingly brief window, and afterwards, Ruggiero and Green never see Project Tech participants again. These days, Ruggiero has to make concessions: Twine instead of Scratch, basics instead of complexities, etc.

Despite all of that, Ruggiero believes that Project Tech can make a difference. She thinks that games can reach incarcerated youth in a way the reductionist rhetoric surrounding them can’t. It’s not that the kids are flunking out of life, she insists. It’s that the system is failing them.

“They’re not stupid kids,” she said. “They’re really not. They’re in trouble a lot, so, because of that, they’re behind in school. They’re behind in what I would consider social bonds, emotional bonds, and they don’t have the wherewithal to say, ‘I need help.’ Then when they get out of jail and they go back to school, they just go back to where they were. We don’t ever have them getting the help that they need.”

Games, though, get them excited, and they can help teach real skills instead of illusory ones. That’s a start. Ruggiero thinks it’s a good one. In an academic paper she sent me, she reported that while youths were initially reluctant—frustrated by the fact that they weren’t making games that looked and played like Grand Theft Auto—the experience got them thinking outside the box. One admitted that creating choices in a story was far more challenging than they expected. Another found the environment more engaging and less intimidating than typical child security center education.

“This is better than going to school, and I can work on the game with no one shouting at me,” they said.

For others, the whole process was eye-opening. They got to flex muscles they didn’t even know they had.

“I learned about narrative games and actually made two games, and I didn’t think I could do that,” said one young person after completing the program.

“You know a lot of stuff has happened to me, and I did a lot of stuff too. Maybe I can make more games now that I know how it works,” said another.